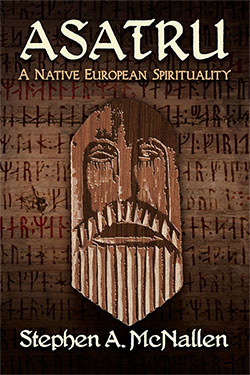

Stephen McNallen's Asatru

A Native European Spirituality

Collin Cleary

The Good Preacher

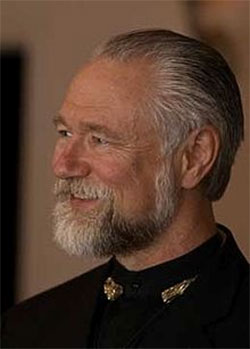

Steve McNallen is a serious character. A former U.S. Army Ranger, he has hitchhiked across the Sahara Desert and traveled to such exotic locales as Tibet and Burma, usually to report on military conflicts. His articles have appeared in Soldier of Fortune magazine (a periodical that fascinated me when I was a teenager, especially the classified ads in the back). McNallen has also worked as a jailer, a juvenile corrections officer, and has served in the National Guard (he was witness to the Rodney King riots back in 1992). Oh, and he taught math and science for six years in an American high school, using his summer vacations like Indiana Jones, setting off on foreign adventures.

Steve McNallen is also the man principally responsible for the revival of Asatru in North America. He gives us a brief overview of his life, written with typical modesty and understatement, in this wonderful new book, several years in the making. McNallen tells us that he decided to follow the gods of his ancestors while he was in college “in either 1968 or 1969.”

I like the honesty of this. A lot of men, if they were uncertain which year it was, would have just picked one, perhaps even giving a specific date: e.g., “Walpurgisnacht 1969!” But McNallen is not concerned to make an impression, or create an image for himself. His sincerity, earnestness, and lack of pretension have a great deal to do with why he has become a genuine religious leader.

A good preacher has the ability to form people into a genuine community through appealing to their better nature. No easy task. And a good preacher establishes his authority not through his book learning or some seal of approval from a Council of Elders, but rather through the force of his personality. Just what that consists in is a complex issue. Partly, it’s a simple matter of “good character.” Aristotle said that one of the necessary conditions of being an effective speaker is that the audience must perceive the speaker as having good character. Otherwise they will not be convinced by what he says, no matter how cogent his arguments are.

However, “force of personality” also involves strength of conviction. A good preacher is someone whose faith is so strong that others believe because he believes. Privately, they may suffer doubts. But just being in the presence of a good preacher, a man with real strength of conviction, is often enough to bolster them. And I do not necessarily mean listening to him preach. A good preacher communicates his faith and sincerity in his every act, even in the way he moves across a room or eats a meal.

I experienced McNallen’s force of personality for the first time one evening several years ago on a beach in California. I was one of about 25 people who gathered together around a bonfire to participate in a blot led by McNallen. It was truly a mixed crowd, running the gamut from university professors to skinheads. I had driven there with McNallen and his wife Sheila, on the way picking up a cake at a local supermarket. My job was to ride shotgun and serve as navigator, directing McNallen to the beach. He was in an extraordinarily good mood and as I gave him each direction (“turn left here . . .” etc.) he responded in crisp military fashion: “Roger that!”

I wasn’t sure how this was going to play out. I am a lone wolf by nature, and Asatru for me has always been a pretty solitary affair. On those occasions when I participated in rituals with others it usually felt like we were LARPing (Live Action Role Playing). In other words, I felt a bit silly. But on the beach something strange and uncanny happened. It was a constellation of factors. One was the natural setting: fall on a northern California beach, nighttime, waves crashing, bonfire crackling and roaring. But the key factor was McNallen. As he spoke, mead horn in his hand, Asatru came alive for me (and, I think, everyone else) in a way it never had before.

I am a philosopher, and that means that my life is mostly about theory. And this is true of my relation to Asatru: theory, to the neglect of practice (though, to be clear, not the total neglect). A few hours prior to heading for the beach, McNallen had asked me what rituals I perform. I confessed to him that I performed few rituals, and very seldom. He seemed disappointed, and I felt slightly ashamed. Such is the power of a good preacher! I had encountered the same disappointment with others on revealing to them my neglect of ritual, and my standard response had been to quip “I’m a Protestant” (i.e., as opposed to a “Catholic” follower of Asatru, who needs rituals and candles and incense). But I knew I couldn’t be so glib with McNallen.

When he led that blot on the beach I felt a real sense of connection to my ancestors, and to the gods. It was a transformative experience. However, it wasn’t a “mystical experience”: I didn’t feel suddenly at one with all things, or that the Being of beings had been revealed to me. No, it was something more basic than this: it was a religious experience. And a key part of this was the presence of others. As I said, it was a constellation of factors. There was the natural setting, and McNallen’s charisma, and the truth that came through his words. But in addition there was an absolutely essential component, without which this religious experience would not have been possible: others — others like me.

A few years ago I wrote a controversial article titled “Asatru and the Political” (it’s included in my recent book What is a Rune? And Other Essays). The major point of the piece was that since Asatru is a folk religion, born of the spirit of European people, we followers of Asatru must take an interest in the survival and flourishing of the race that gave rise to it. In short, I argued that commitment to Asatru entails what is sometimes called today “white nationalism” (not the same thing, as I explain in the essay, as “white supremacism”). In Asatru: A Native European Spirituality, McNallen makes essentially the same point (without using the term “white nationalism”). I hasten to add that McNallen was making such arguments long before I was — a point to which I will return later.

In any case, in that same essay I argued that every religion is really a way in which a people confronts itself, for every religion is an expression of a people’s spirit, born of the encounter between a distinct ethnic group, with its own inherent (i.e., genetic) characteristics and a place. What I did not emphasize is a corollary point: that religion is inherently communal. It is often asserted that the word “religion” comes from a root meaning “to bind,” and on this basis it has been speculated that “religion” means “to bind together.” If this is correct (and no one really knows), two interpretations are possible. The first is that religion binds or connects individuals to the divine (sort of like the literal meaning of “yoga,” as that which yokes us to the divine). The second is that religion binds us together in a community.

Anthropologists and sociologists favor the latter interpretation, with some going so far as to suggest that the “purpose” of religion is really nothing more than making communities cohesive. This is a vulgar, flat-souled notion that I discuss elsewhere (see my essay “The Stones Cry Out,” also in What is a Rune?). The truth is that religion binds together a community, through binding it to the divine. Both of the interpretations just mentioned are correct. Through religion, I achieve connection with the gods — but that is only possible through connection with others who have the same aim, and worship the same gods.

Religion is not the only way of making some “connection” to the divine. Mysticism is another way. So are philosophy and theology. Even art and poetry are means. But these can all be solitary activities. We may want an audience for our poetry (or our philosophy), but we don’t need one in order for poetry (or philosophy) to occur.

For religion to “occur” we need others. There can be no such thing as a private religion. Elsewhere I have discussed at length my commitment to Odinism (see “What is Odinism?” in Tyr Volume 4). Odinism is the path of one who follows Odin — really of one who seeks to become him. It is not about “worshipping” Odin, and it is not a religion. It would be accurate to call Odinism (as I define it[1]) a cult within Asatru. Though by its very nature it is a cult arguably best suited for lone individuals (at least, that’s how it is for me): a cult whose “cells” consist of isolated individuals. Until that night on the beach in California, Odinism really was Asatru for me. It was when the blot had ended that I realized my error.

What happened when the blot ended? There was silence. We ate our cake and sat around the bonfire, speaking in hushed tones. There was a kind of electricity in the air, and I think I speak for everyone there when I say that I felt lifted out of myself. I felt connected. Connected to the divine but also — and this is very unusual for me — connected to the others. I felt part of a religious community. It was then that I realized that my Odinism, while entirely legitimate, was not enough.

Imagine the absurdity of a Christian theologian who said that the practice of theology was sufficient unto itself and that he had no need of belonging to a church. But this was exactly my own position: an Odinist, a Germanic neo-pagan philosopher who never practiced his neo-paganism. And by “practice” here I mean practice with others. I was an irreligious neo-pagan. A Protestant indeed.

Of course, there’s an Odinic response to this — or one that seems plausibly Odinic: “Odin is the lone wanderer, he does not need others. If you aspire to be Odin, you do not need blots and such.” But there are two problems here. First, Odin clearly needed the company of the other gods: he returned to them from his wanderings again and again. The second problem is that while there is a part of me that is Odin, and my Odinism is the cultivation of this (again, see my essay in Tyr #4), it is only a part of me. I am still a man, and man is a social animal. And the supreme, most elevated and sublime aspect of his sociability is his religiosity. My experience on the beach didn’t teach me that I ought to come together with others and practice Asatru; it taught me that I needed to, but hadn’t been aware of the need.

Of course, the blot on the beach and the important realization I had there was more than three years ago. And I am still a lone Odinist, keeping an eye on Asatru from the periphery but seldom ever joining with others. Old habits die hard. There are many people who have a much stronger desire to come together with others than I do, but simply cannot because they don’t live near anyone. In one way I am not alone: many of us have been solitary cultists, for a great many years. Then there’s that other big problem: sometimes when you meet others who claim to follow Asatru you are very, very disappointed.

The Rise and Fall and Rise of the AFA

But all of this seems to be changing. And primarily we have Steve McNallen to thank for it. McNallen is well aware that Asatru must be about community; that the solitary practice of Asatru is ultimately insufficient. In recent years, there have been more and more occasions for people who follow the ancestral gods to come together. More people — serious, sincere, and sane people — are being drawn to Asatru and forming local kindreds, or assemblies. McNallen’s organization, the Asatru Folk Assembly (AFA) has organized several events each year for a number of years now. The most successful of these have been “Winter Nights in the Poconos,” held in the fall at a camp in Pennsylvania. And, of course, the internet is helping people to find each other.

McNallen’s own experience of Asatru — which he narrates in this new book — is one that also began in isolation. As noted earlier, McNallen decided to follow the gods of his ancestors when he was in college in the late sixties, serving in the ROTC. This was the Age of Aquarius, and I was in diapers. But I was nonetheless very much aware of the “Occult Revival” when I was a small child in the early seventies. I still remember the weird shop in the strip mall, down the block from Rose’s Department Store, where (at the age of eight or so) I bought my copies of The Sorcerers Handbook and Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. (However, once my mother figured out that it was also a head shop she stopped letting me go in there.) Wicca was certainly on the scene, but Asatru was nowhere to be found.

McNallen thought that he was totally alone. In desperation, he took out ads in magazines like Fate, looking for others like himself. Slowly, he formed a small group which he called the Viking Brotherhood: the first Asatru organization in the U.S. McNallen began publishing his own periodical, The Runestone, in 1971, and by the following year the Viking Brotherhood had become a tax-exempt religious organization. He told me once that at the time he and his comrades were making Thor’s hammers out of the keys from sardine cans. (Today, of course, Thor’s hammers are available with two-day Prime shipping from Amazon — largely thanks to McNallen spreading the faith.)

But almost as soon as he had launched the Viking Brotherhood, McNallen had to report for active duty as an officer in the Army. Needless to say, this severely restricted his work on behalf of Asatru. At the time, by the way, Asatru was not Asatru. McNallen did not begin using that term until 1976, after reading it in a book by Magnus Magnusson. Up until then, he had called his religion “Norse Paganism,” or sometimes “Odinism.” It is important to note that our ancestors did not have a name for their religion at all. (“Asatru” which means “true to the Aesir,” is a term coined in the 19th century.)

Names for religions have come into use as a result of the rise of universalist faiths like Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. These religions needed to call themselves something because they imparted an ideology, and sought to convert people away from their folk religions: they needed to be able to approach people and say “we represent x.” As to the names traditionally given to folk or ethic religions, typically they do not distinguish a member of the ethnic group from an adherent to the religion. The term “Hinduism” is derived from the Persian word “Hindu,” which actually just denotes the Indian people. The etymology of “Judaism” is similar, derived from a word that simply means “Jew.”

By all rights, Asatru — which is an ethnic religion — ought to be called “Germanism,” or “Teutonism,” or something like that. Though both of these are problematic choices, for a number of reasons. But “Asatru” is problematic as well (though it looks like we are stuck with it — which is fine). Imagine if Judaism changed its name to “Yahwism,” the religion of those who worship Yahweh.[2] Inevitably, along would come a gentile who felt entitled to describe himself as a “Yahwist,” because he has decided to worship Yahweh. But if “Yahwist” had the same denotation as “Jewish,” he would have to be taken aside and politely told that the Yahwists are a people, a tribe, not just a collection of believers in a particular theology. And so he cannot be a Yahwist. (Wisely, the Jews — like most Hindus — have remained aware of the ethnic identity of their religion, and are not particularly eager to embrace converts.)

Our term “Asatru” invites a similar problem. If the religion is literally being “true to the Aesir” (“true” as in being loyal to or believing in) well then why can’t a man whose ancestors came from Niger decide that he wants to be true to Odin, Freya, and Thor? McNallen came to face this problem squarely in the seventies:

It was in about 1974 that I began to realize that there was an innate connection between Germanic paganism and the Germanic people. I had resisted the idea as being somehow racist, but I could not ignore the evidence. Within a year or two I had shifted from a “universalist” to a “folkish” position — even though neither of those terms would enter our vocabulary for many years. (pp. 62-63)

It was around the time that McNallen adopted the term “Asatru,” after his discharge from the Army, that he formed the Asatru Free Assembly as successor to the Viking Brotherhood. This is not to be confused with the Asatru Folk Assembly, his present organization. As the above quotation implies, the folkishness of the “first AFA” was largely implicit, for the simple reason that McNallen was surrounded by like-minded people. The Asatru Free Assembly went from being a small group meeting in the back of an insurance agency in Berkeley, California, to a national organization. It published booklets and audio tapes, and beginning in 1980 held an annual summit, the Althing. “Guilds” formed within the first AFA, each with its own newsletter.

There was no other Asatru organization in North America until the mid-1980s. The AFA was it. But by the mid-’80s it was dying. McNallen and his wife were both holding down full-time jobs, and trying to run the AFA on the side. The ideal situation, of course, would have been if they could have turned the AFA into their full-time work. But when they tried that, soliciting financial support from AFA members, they were accused of being “money hungry.” Some people just expect something for nothing. (A problem with which the editor of this website is all too familiar.) It was an impossible situation, and eventually McNallen had to close the AFA, the remains of which morphed (with his blessing) into Valgard Murray’s Asatru Alliance.

Then came McNallen’s years of wandering, writing for Soldier of Fortune, interviewing Tibetan resistance fighters, serving in the National Guard. With characteristic frankness, he admits that while he never wavered from being true to the Aesir during this period, the collapse of the first AFA left him quite bitter. For a long time, he simply gave up on being involved (at least in a leadership capacity) with organized Asatru. What drew him back in was precisely the realization that circumstances had forced those true to the Aesir to make explicit what had been the movement’s implicit folkishness. McNallen writes:

In 1994, I saw signs that a corrupt faction was making inroads into the Germanic religious movement in the United States. Individuals and groups had emerged which denied the innate connection of Germanic religion and Germanic people, saying in effect that ancestral heritage did not matter. This error could not be allowed to become dominant. I decided to reenter the fray and throw my influence behind Asatru as it had been practiced in America since the founding of the Viking Brotherhood back in the 1970s. I formed the Asatru Folk Assembly. (pp. 65-66)

The change from “Free” to “Folk” made things pretty explicit. (And, I will add, has the further advantage of disabusing those who thought that commitment to Asatru cost nothing.) McNallen is too much of a gentleman to name names here, but the “corrupt faction” he is referring to is typified by folks (and I use the term loosely) like the ultra-PC “Ring of Troth,” who are truer to the Frankfurt School than to the Aesir. I won’t say anything else about such people here, as their attempt to turn Asatru into a universalist creed is unworthy of serious discussion.

Article Two of the Declaration of Purpose of the Asatru Folk Assembly states:

Ours is an ancestral religion, one passed down to us from our forebears from ancient times and thus tailored to our unique makeup. Its spirit is inherent in us as a people. If the People of the North ceased to exist, Asatru would likewise no longer exist. It is our will that we not only survive, but thrive, and continue our upward evolution in the direction of the Infinite. All native religions spring from the unique collective soul of a particular people. Religions are not arbitrary or accidental; body, mind and spirit are all shaped by the evolutionary history of the group and are thus interrelated. Asatru is not just what we believe, it is what we are. Therefore, the survival and welfare of the Northern European peoples as a cultural and biological group is a religious imperative for the AFA.

As always, the cunning of reason — or the hand of the gods — has been at work: as I noted earlier, the new AFA has wings the old AFA never possessed. If the old organization had never fallen apart, and McNallen had not lived his wilderness years, we would never have seen the birth of the Asatru Folk Assembly, and the Asatru Renaissance that it has helped bring about.

There is more to the tale of the new AFA — such as the saga of its involvement in the “Kennewick Man” controversy — but for the rest you will have to read the book.

Asatru: A Native European Spirituality fills a void. It is intended to introduce readers to Asatru — readers with no prior acquaintance. As such, it is written in a highly-accessible style. And yet there is much here that will be of interest to those already well acquainted with Asatru: the fruits of almost 50 years not just of McNallen’s experience as a leader and exponent of Asatru, but of his deep reflection upon the meaning of the religion, and its integral relation to the Northern European peoples and their spirit. There is no other book I know of that is as comprehensive and illuminating an introduction to folkish Asatru.

Why Asatru?

Before I close this review there is one more issue that I need to address. There is a tendency among those in the New Right to either embrace Asatru, or simply to tolerate it (usually on the basis that it might — repeat, might — be a useful political tool). Those who tolerate it typically think it’s a bit silly — or at least not something for them. And so a lot of my readers may find this review interesting, but conclude that McNallen’s book and the AFA are for those already converted. I’d like to encourage those folks to think about things differently.

McNallen actually takes no position on whether or not the gods “really exist.” In the AFA, one can be a “hard polytheist,” who actually believes there’s an Odin riding around out there on Sleipner, or a “soft polytheist” who thinks the gods are inflections of some ultimate Brahman-like principle — or even that they are just poetic constructs that hold up a mirror to our Northern souls. There are tricky issues here, and my own position doesn’t readily fall into any of these categories. But one thing is certain: whether or not the gods “really exist,” the gods and the myths about them most certainly do poetically mirror our Northern souls. This is the first thing I’d like New Right “sceptics” about Asatru to consider. Asatru is us.

As I put it in my essay “Asatru and the Political”:

Ásatrú is an expression of the unique spirit of the Germanic peoples. And one could also plausibly claim that the spirit of the Germanic peoples just is Ásatrú, understanding its myth and lore simply as a way in which the people projects its spirit before itself, in concrete form. And this leads me back to where I began, to the “political” point of this essay: to value Ásatrú is to value the people of Ásatrú; to value their survival, their distinctness, and their flourishing. For one cannot have the one without the other.

Here I was enjoining followers of Asatru to defend the interests of people of European ancestry. But now I am enjoining those who already believe in that cause to value Asatru. Because, you see, valuing “the people of Asatru” — European (or Northern European) people — must mean, at its most basic level, coming together with them in a community.

What Asatru offers to the New Right is a community of people of European ancestry focused around the celebration of that ancestry, and common culture. I have already discussed the progress the AFA has made in building this community — in genuinely bringing people together. McNallen writes:

We console each other in times of death, and celebrate the birth of new children. We share favorite books, career tips, and recipes. We make plans to meet down at a local pub, or to attend an event the next state over. Locally, we gather for rituals and for birthday parties, or to load a truck for someone moving to a new home. (p. 69)

The Fourth Article of the AFA’s Declaration of Purpose states that it is devoted to “The restoration of community, the banishment of alienation, and the establishment of natural and just relations among our people.” The banishment of alienation — the condition so many of us on the Right suffer from. And often it is our own doing. The idea of a community of people of European ancestry celebrating that ancestry sounds really good — but there’s all that stuff about Odin . . .

Well, I mentioned earlier that I come from a long line of Methodists. And my mother attended the local Methodist church all her life. But here’s something that will surprise you: she wasn’t particularly “religious.” Yes, she believed in God and in Heaven in some sense, and she thought that the Bible was mostly a good influence on people (though I think she never read it). But my mother thought it unbecoming to carry things to extremes. In particular she looked down on people who talked about Jesus all the time: “Jesus loves you” made her flesh crawl. She thought that people who talked that way were a bit “touched” (in the bad sense), and a bit low class.

For my mother, church was about community. It was a place where you met what she called “decent people,” and often had the satisfaction of helping each other. It was a place where people were brought together by a shared desire, to one degree or another, to orient their lives to an ideal (or at least to be seen to be doing so). And it was a place where people were brought together by common ancestry — for my mother’s church was implicitly white (a fact she would have readily admitted). Yes, some of the people there were, in her eyes, a little too “Jesusy.” And others not enough. Some took the Bible just a little too seriously, and said and did peculiar things. They were cranks. But in my mother’s eyes they were “our cranks.” She derived enormous satisfaction and comfort from her participation in that community. This was something I didn’t understand until much later in life.

So, if you are skeptical about Asatru just start here — I mean just with the kind of tentative, minimalist recommendation I’ve made in the last few paragraphs. Asatru as a community of people like you. This is actually quite a lot. More may come later. Or perhaps not. Perhaps you’ll always think that people who talk about Odin are a bit “touched.” But you’ll be with your people; with people who are aware that they are your people. As Steve McNallen says in this book, “Asatru is about roots. It’s about connections. It’s about coming home.”

http://asatrufolkassembly.org/

Notes

1. I derive my understanding of Odinism from Edred Thorsson. See Edred Thorsson, Runelore: A Handbook of Esoteric Runology (York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1987), 179.

2. This term actually is used by scholars, to denote the cult of Yahweh among the ancient Hebrews — the cult that eventually became Judaism.