Religion for Infidels

Anthony M. Ludovici

Editor's Note:

Religion for Infidels (London: Holborn, 1961) was Anthony Ludovici's last book (as opposed to essay collection). In it, he addresses the increasing population of individuals who have religious or spiritual inclinations and yet find it impossible to believe in revealed religions such as Christianity.

John Day's The Lost Philosopher: The Best of Anthony M. Ludovici (Berkeley, Cal.: ETSF, 2003), contains well-chosen selections from Religion for Infidels which present its argument in abridged form. I am reprinting those selections in five parts.

Part 1 of 5

Because of the difficulty most thoughtful men now have in accepting orthodox religion, and the deprivation they inevitably suffer in living without any religion whatsoever, the time seems to have come when some attempt should be made to provide at least a rough outline of a possible religion for so-called ‘infidels’—the men and women who cannot believe in Christianity and who nevertheless are far from willing to remain destitute of any concern about transcendental questions. (Religion for Infidels, p. 9)If we knew all there is to know about life and the universe, including their origin, and were as well-informed about our own provenance and purpose as we are about those of the cars we drive, it is probable that what we understand by religion would either have much less importance than it has at present, or else would wear so different a mien as hardly to be recognized as religion by the modern churchman.

For the principal source of all religious belief, and of the particular claims of different religions, is the hidden, inexplicable character of both our world and our existence in it. This presents such a formidable barrier to a satisfying grasp of all that we see and feel about us that the effort to rid ourselves once and for all of the agonizing uncertainty of our knowledge about ourselves, our destiny and our surroundings drives us, or at least the more thoughtful among us, to clutch, often with undue haste, at any answer to our endless questionings provided that it is tolerably plausible. And it is this plausible and usually provisional answer that gives us the basis of our religion and determines its character.

Whence do we and the universe come? Whither are we going? Why are we here? How did life originate? What means the immeasurable vastness in which we are but a negligible speck? Why this infinite multitude of heavenly bodies? What is the purpose of it all? Is the very idea of purpose an illusion? Is everything meaningless, pointless and the sport of chance and accident?

Every fresh generation of men asks these questions, and no progress is made in answering them. Even modern science, despite its many staggering and spectacular advances, cannot help us here. Indeed, when the reading-public learn of the latest findings of the astronomers, physicists, geophysicists and philosophers, their wonderment and mystification are magnified rather than diminished. Compared with the relatively simple account of the origin of life and the universe with which our forebears of a hundred years and more ago were content, present-day scientific theories about our origin and our psychophysical nature are so complex, unbelievably fantastic and, above all, so lacking in unanimity that those moderns who are too intelligent to take anything for granted, who still retain the power to wonder and wish to be enlightened concerning the universe and themselves, may be forgiven if in the end the replies they get to their anxious inquiries leave them more baffled than illuminated. (Religion for Infidels, pp. 17–18)

Agnosticism ... may be a comfortless refuge from the countless riddles that incessantly taunt human curiosity, but, if he can control himself when tempting alternatives occur to him, it is the only course open to the man who, abreast of the latest speculations of science, is scrupulously honest in intellectual matters ...

Whether the decline in Christian worshippers is to be ascribed to the slow saturation of the Western atmosphere with the views of science or to the general and steady loss of intelligence throughout the population, a loss which inevitably blinds increasing numbers of commonplace folk to the challenging problems of the world about them, cannot be determined .. .

Macneile Dixon ... thinks ‘the decay of religious faith is due to the increase of our positive knowledge’ ... whilst Dr Joad, apparently of the same opinion, maintains that ‘it is a comparatively rare thing to find an educated man who is also a Christian’ ... But, as we have seen, there are other contributory factors, and I submit that, in addition to the increase in stupidity, there has been in recent years, especially in the Western world, a marked increase in superficiality and levity. This may represent only one facet of the increase of stupidity, although it may more probably derive from the substantial decline in passion and temperamental vigour, which in itself is the outcome of the general decline in stamina throughout the populations of the West. (Religion for Infidels, pp. 24–6)

In reply to the question, ‘What passion can explain an effect of such mighty consequence as religion?’, [David Hume] replies, ‘Not speculative curiosity merely, or the pure love of truth, but’—and what follows may be briefly summarized as ‘fear’ ... This is also Bertrand Russell’s opinion. ‘Fear’, he says, ‘is the basis of the whole thing, fear of the mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death’ ... whilst even William James seems to lend it some countenance when he says: ‘The ancient saying that the first maker of the gods was fear receives voluminous corroboration from every age of religious history’ ... If man were encompassed only by dangers which drove him to implore the protection of benign supernatural forces against their opposite, fear would adequately explain the matter.

But man, and above all unscientific and ignorant man, is also surrounded by wonders not necessarily always of a menacing kind. Everywhere, his senses apprehend something that he can neither do, control nor understand, and we have but to observe the overpowering curiosity of the lower animals, which makes even the least intelligent of them, let alone the cat and the dog, incur danger in order to examine and search the origin of an unfamiliar object or sound, to become convinced that man is hardly likely to be less irresistibly impelled by his curiosity. As Professor J.B. Pratt remarks, curiosity ‘exists alike in the scientist and in the savage, in the monkey and in the dog’ . . .

If, then, we conclude that religion is probably a blend of both curiosity and fear, it seems justifiable to assume that as man’s mastery over Nature gradually increased until it established him in the relatively secure position he has enjoyed for several centuries, at least in the civilized world, the factor curiosity is probably that which has recently played the predominant part in fostering the religious attitude of mind.

Thus, at bottom, religion satisfies two major human needs: it answers man’s questions about origins, and furnishes him with guesses about the ‘power behind phenomena’ and his relationship to that power. These are religion’s fundamental meaning and function, and its most essential features are probably its tenets concerning the power in question and man’s relationship to it. For, given the fact of such a power, nothing could be more vitally important than to know what to expect of it, what it expects of man and how to obtain contact with it. (Religion for Infidels, pp. 27–8)

Here, on this planet Earth, we are very much like a group of aviators flying above the clouds. Their safety depends essentially on accurate estimates of the direction, strength and possible variations of the invisible wind, of the temperature and chemical composition of the invisible atmosphere, and of their altitude and position in an area destitute of visible signposts. In the same way, we on this planet, alone in the vast universe, will be more likely to avoid disaster or destruction, at least in our individual lives, if we try to understand something about the invisible forces about us, and, above all, how they work, than if we omit to find out anything about them . . .

A merely urban knowledge of life, even when it includes an intimate acquaintance with humanity, may hardly suffice for an adequate picture of what animate Nature implies and what primary forces invisibly control her machinery. Given a high degree of sensitiveness and intelligence, it is conceivable that even a confirmed townsman might, without the panorama of vital phenomena as it is unrolled in all its rich manifoldness along the countryside, reach fairly shrewd notions about the basic trends of the invisible forces directing living things on Earth. Indeed, Lao Tzu, of the sixth century BC, actually maintained that merely by silent meditation one might become master of all worldly wisdom.

But, generally speaking, in order to reach fruitful conclusions concerning these questions it is desirable to have lived for years where, alone in civilized communities today, one may view life with approximate accuracy, because it is still, as it were, naked, opulent and varied enough, both in the animal and vegetable realms, to reveal its secrets.

Then, unless one resembles too closely the tired, listless and Nature-surfeited peasant, certain precious discoveries cannot escape one, and among the more striking of these is the fact that behind the visible phenomena of the daily scene unmistakable prevailing trends become noticeable. They appear like pervasive rules of procedure, governing life’s processes in both animals and plants, and are as unexpectedly different from our superficial first assumptions as they possibly could be. Ultimately they seem to merge into one universal trend or bias, which appears to us as a cosmic influence informing all living things, and it can be so precisely recognized that its attributes and their manner of operation may be clearly defined.

Let us therefore explore the vast panorama of Nature as displayed in our small world alone, without troubling ourselves with its manifestations elsewhere, and see what evidence we can find of any distinctive attributes whatsoever which may help us to understand the invisible forces governing life’s processes.

Part 2 of 5

As a result of a close and steady observation of [natural forces], above all as they reveal themselves in the behaviour of living things, we feel entitled to draw the following conclusions:

(a) They give fair field and no favour to all alike, no matter of what kind. This is shown not only by the indiscriminate attacks of pathogenic organisms on both men and animals, not only by the enormous amount of distress, irritation, pain and even lethal disease which may afflict both men and animals through the action of microorganisms and insects of all kinds, and not only by the bellum omnium contra omnes [the war of all against all] that never ceases among plants and animals, but also by the multitude and wide dissemination of parasitic organisms. L.A. Borradaile tells us, for instance, that ‘from the amoeba to man there is probably no animal which is not attacked by some parasite and, and as many species of parasite are confined to one host, it is probable that parasitic animals are not greatly inferior in numbers to all the others together, though their habits prevent the fact from being generally realized’ . . .

(b) They are quite indifferent regarding what we human beings of a late civilization call ‘quality’. In other words, they show no ‘taste’ or fine discrimination in our sense. This is shown by the vast amount of what we cannot help considering as ‘ugly’ or ‘repulsive’ features in Nature. Indeed, the whole gamut of her achievements, from the transcendent beauty of some of the cats down to the least attractive of her batrachians and gastropods, some venomous snakes, some fishes, and ‘certain hideous bats’ (The Origin of Species, chapter 15), seems to indicate that no distinguishable inclination to beauty rather than to ugliness characterizes the life-processes, and that what appears to take place is a random production of either, according to the exigencies of the evolutionary hazards.

(c) They give no sign of favouring any upward trend in the evolution of living things, whether plants or animals. ‘Natural selection’ occurs destitute of all civilized humanity’s estimates of desirability. Indeed, the evolutionary steps securing survival are so often steps downward or backward that the examples of ‘retrograde metamorphosis’ in Nature, as Spencer pointed out some ninety years ago, ‘outnumber all others’ . . .

(d) A more dynamic and upsetting principle than the so-called ‘struggle for existence’ (urged on by the self-preservative instinct) or, as Schopenhauer termed it, ‘the will to live’ animates all living creatures and plant life, and the forces governing life’s processes have implanted in all their creatures a will much more extensive, which takes the ‘will to live’ in its stride.

For we see animals and plants doing not merely the bare necessary to keep alive, but also everything possible with the view of overcoming other species. They do not merely sustain their own lives; they obtrude themselves on other lives, even other lives belonging to their own species. They all assault, invade and trespass on alien territory. We need only watch them for a little while in order to be convinced of the error of assuming existence as the be-all and end-all of their striving. For what soon strikes us—chiefly in contemplating animals, even quite young ones—is that they feel above all, and coûte que coûte [at all costs], the need to discharge their strength, to make something else pay for their good fettle and high spirits. Their first concern, as soon as they stir, is to importune their surroundings, to enjoy using and expressing energy, if possible at the cost of some other life—that is to say, in overpowering, subduing or merely intimidating and scaring other creatures.

The unleashed dog rouses the neighbourhood with his bark, seizes a fallen branch and shakes it, growling angrily the while. He charges other dogs on his path, fights them and chases every creature within sight. He will even chase and try to bully the fast-revolving wheels of a passing car. He revels in his strength and fleetness . . .

Indeed, we have the highest authority for declining to set man outside Nature. Even if it may be extravagant to claim that Nature has become wholly conscious in him, his affinity to her as her child makes him as reliable an exponent of her deepest currents and trends as any animal or plant. Here most thinkers are in agreement with Professor A.N. Whitehead, who stated the case with commendable clarity when he said: ‘It is a false dichotomy to think of Nature and man. Mankind is that factor in Nature which exhibits in its most intense form the plasticity of Nature’ . . .

Thus, when we inquire of the deepest thinkers, ‘What is Nature’s most fundamental urge as manifested in man?’, we are not surprised to find them confirming the conclusions we have formed from our survey of animals and plants, and supporting the generalizations of both Plato and Nietzsche.

Aristotle says outright that all men aspire to ascendancy . . . Hobbes unhesitatingly concurs. ‘I put for a general inclination of all mankind’, he says, ‘a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death’ . . . In the discourse entitled ‘Von der Selbst-Ueberwindung’ (On Self-Mastery) in Thus Spake Zarathustra, Nietzsche expounds the doctrine of the will to power as basic in man. But the principle is repeated in all his works and, especially in the two posthumous volumes of The Will to Power, is postulated of the universe in general . . .

So there appear to be substantial grounds for the view that a striving after supremacy or power is the basic trend of all Nature, and that Schopenhauer’s ‘will to live’, like the ‘struggle for existence’ of our nineteenth-century biologists, gives but an inadequate idea of the radical trend of the forces governing life’s processes. In other words, there is more in these forces than a mere readiness to vegetate or survive even on a lavish scale, and, unless we turn a blind eye to most of the more disturbing, importunate and gratuitously obtrusive tendencies of both animals and plants, we are constrained to postulate a basic drive in Nature, more dynamic, convulsive, upsetting and consequently, of course, more ‘evil’ than merely the will to persist and keep one’s head above water.

Indeed, it must have struck the kind of thinker who has been led to read the will to power between the lines of Nature’s picture-book that it is otiose and romantic to hope ever to overcome what the moral idealists in our society regard as ‘evil’, unless means are found for uprooting from the character of every living thing, including man, this fundamental drive, acknowledged by many leading modern psychologists to be the will to power.

What can be the good, then, of speaking of ‘eternal peace’, or a future of ‘loving concord’ for all mankind, or of any state in which rivalry of some kind, violence, high-handed appropriation and expropriation, oppression of some kind, and discord have been wholly eliminated? What possible trace of realism remains in Shaw’s attribution of all wickedness to poverty, or in Marx’s implication that what men call ‘evil’ will disappear when once a classless society is established? . . .

To hold typically liberal views, therefore, and to assume that if we liked we could all settle down to love one another and live in perfect amity and harmony together, is possible only to those idealists who are congenitally blind to the true character of all life; whilst, as for those numbskulls who begin to see and think of the will to power only when figures like Napoleon, Stalin or Hitler appear, and who overlook it wholly in themselves, their wives, their children and their cat, they are even more dangerous than the idealists aforesaid, because they scent and suspect an awkward and unamiable feature of existence only when it is already thundering down upon them, and are like people who are not aware of the volcano at the end of their garden before they and their home are smothered in tons of burning lava.

It is very probable, however, that this one dynamic factor informing all living matter—the will to power—may be the major, if not the only, element in the life-forces which, by constantly contending with and often defeating the trends implicit in factors (a), (b) and (c), whose influence, if not actually favouring degeneration and survival by backward rather than forward steps, at least offers no potent resistance to it, has accounted for all those triumphs of the evolutionary process, all those relatively rare but upward and progressive changes in both the vegetable and animal kingdoms that have culminated in producing the highest examples still extant of our plants and living creatures, including even man himself . . .

(e) The fifth conclusion which it seems to me legitimate to draw concerning the forces behind phenomena relates to their amorality, or their lack of all those moral principles with which civilized societies regulate human intercourse.It hardly needs saying that in all Nature there is no trace of any such morality. On the contrary, every kind of thuggery, deception, fraud, duplicity and mendacity finds its ablest and most unscrupulous exponents in Nature. It is true that much of this criminality is designed to protect the creatures practising it, just as much of the thuggery contributes to their survival, but the practices in question remain dishonest and immoral (in our sense) notwithstanding. We find caterpillars imitating twigs to such perfection that their worst enemies fail to recognize them. We also see butterflies mimicking dried leaves and beetles resembling moss so exactly that their disguise completely deludes the rest of living creatures. On the other hand, we find innumerable species of harmless animals and insects protecting themselves by resembling noxious or dangerous species, or by actually descending to the ruse of representing excrement. The drone-fly, thanks to its mimicry of the large hive- or honey-bee, which is distasteful and has a sting, is left entirely alone. Many edible insects, in fact, save their lives by masquerading as inedible ones; among them are several species of ants, beetles and spiders. In animals, a good example of the same phenomenon is the little bush-dog of Guiana and Brazil, which, by closely approximating to the form and colour of the weasel-like tayra, protects himself from the attacks of pumas, jaguars and ocelots.

Often the deceptive mimicry works the other way about—that is to say, not to protect an insect or animal but to hoodwink its prey. Thus, the camouflage of stripes or cloudy patches on many cats’ coats, including those of the tiger and leopard, by imitating the play of light and shade in long grass or brushwood enables beasts of prey to approach the quarry, or to lie in ambush for it, whilst remaining unobserved. An Oriental tree-shrew, by its likeness to a squirrel, is enabled to approach and pounce on small birds or animals which mistake it for a vegetable-feeding squirrel. But of all these devices, whether for facilitating or preventing capture, the fundamental feature is their mendacity, their intent to defraud, and this, in some form or another, is common to all life . . .

It is thus as hopeless to seek the sources of human morality in Nature as to try along evolutionary lines to derive it from obscure rudiments in natural phenomena. To this, however, it may be objected that since, as I have argued, man is not to be separated from Nature, his morality must be natural.

This is of course true. But it is natural only in the sense that honey or silk or a pearl is natural. Like them, however, it is a peculiar product of a particular species in special circumstances and not necessarily repeated elsewhere. In the social life of man, morality becomes a means, sine qua non, of regulating the customary conduct that made communal survival possible; hence the name. It curbed the instincts where they threatened to interfere with conduct that promoted orderly communal life, and controlled primitive impulses so as to adapt them to social order. Consequently, in the world of Nature, which is entirely run by instinct, morality plays no role and is not required to play any. Could it play such a role it would be wholly destructive. It is therefore not a necessarily pervasive feature of natural life and can no more be postulated of all Nature than can honey or silk. Indeed, except for theological purposes, there seems to be no reason whatsoever to extend its incidence outside human societies, and only sentimentalists feel the need of imagining it mirrored in the world about them. From the point of view of the man investigating the attributes of the forces governing life’s processes, it is thus only misleading to speak of Nature as ‘amoral’ for, to us humans, Nature, unless we wish to mince matters, is frankly immoral and behaves in a way that conflicts radically with what is called ‘moral’ in our societies . . .

Part 3 of 5

Part 3 of 5

(f) The sixth conclusion to which a steady and careful study of Nature inevitably leads us is that wherever there is living matter, whether in the human brain or in a blade of grass, there also shall we find intelligence. Every particle of live matter is, we know, composed of cells which, individually and by the simple fact that they are alive, give evidence of intelligent activity. In fact, we are compelled to look on life and intelligence as so inextricably welded together as to be thought of only as coextensive.

At this moment of history, with everyone steeped in the dualistic doctrine that views the living world as consisting of matter and mind, it is difficult to imagine and to affirm the indissoluble unity of these two aspects of life. Willy-nilly, however, unable as we may feel to separate living matter from intelligence, we nevertheless find ourselves insensibly inclining to the view that it is twofold. So long have we been inured to the false dichotomy, ‘body and soul’, that we see it mirrored everywhere, despite our knowledge of the fact that it implies a separateness of which we have not the slightest evidence . . .

To speak of the life of even the simplest protozoan, or of the lowliest cell in any animal or vegetable body, is therefore tantamount to asserting both its vitality and intelligence. For it turns out that there is no knowledge of the two ever being asunder. No matter what comfort this may incidentally afford to morons, it cannot be too emphatically stated that to assume any dualism here, as even the most distinguished scientists and philosophers are wont to do, is to commit oneself to endless confusions and to inferences for which there are no incontestable grounds. To return for the moment to the moron, it therefore seems probable that whilst perhaps his highest rational faculties may be defective, his individual body cells, of which he is alleged to possess about 60 billion, must certainly retain their intelligence, otherwise he would cease to live.

The sixteenth-century wizard, Giordano Bruno, knew this intuitively. He was so deeply convinced that intelligence was ubiquitous throughout the whole structure of the universe that in 1587 he declared it the property even of ‘stones and the most imperfect things’ . . . Nor, if we accept the evolutionary theory, is it possible to doubt what must four centuries ago have appeared the most extravagant nonsense. For if, as all evolutionists agree, at some time or other organic must have sprung from inorganic matter, and if the former is in every sense conterminous with intelligence, a primordial and rudimentary form of intelligence must have been latent and inherent in ‘stones and the most imperfect things’ . . .

Even if we deny these body-cells intelligence, we must at least grant them memory—the remembrance of the work which for eons they have been called upon to perform, whether for constant maintenance, repair or the construction of whole organs. It was evidently some such thought that led Dr Ewald Hering, the eminent German physiologist, to postulate ‘memory as a general function of organic matter’ . . .

(g) The seventh conclusion to which, by innumerable signs, Nature eventually directs us is that, as far as we are able to judge, the forces governing life’s processes are omnipotent and inexhaustible in their resourcefulness. From the infinite variety of their expedients and inventions we are bound to infer that nothing is impossible to them. The unfailing brilliance of their solutions of the most baffling problems partakes in our eyes of the quality of magic . . .

There is in fact no problem, however abstruse and apparently insoluble, which we do not see the forces of Nature solve with the utmost virtuosity, and in contemplating the infallibility of their methods we are driven willy-nilly to the conviction that an intelligence very much higher than any we know must be a pervasive quality of living matter.

From the smallest mammal—the English Lesser Shrew (Sorex pygmacus), hardly two inches in length and a little over an ounce in weight—to the largest of all—the Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus), which may be 89 feet long, whose liver alone weighs a ton, whose heart weighs 1000 lb and whose total weight is 136 tons (i.e., the total weight of twenty-seven elephants)—we find in the animal world alone so much at which to stare in speechless wonder, and so many conundrums brilliantly solved, that we abandon all doubt concerning the uncanny omnipotence of Nature's life-forces . . .

(h)We now come to the seventh major conclusion concerning the attributes of the life-forces deduced from a study of living beings, and, as this conclusion is the outcome of a narrow scrutiny of the factors of organic evolution, we are here probably on the trail of the most secret methods by which the life-forces achieve their ends.The fact that all species of plants and animals, from the lowest to the highest, have in the course of ages evolved from some kind of primordial matter which must have come into existence—how, we do not know—via an assumed series of transformations, from dust, through crystals, enzymes and filterable viruses, is now admitted by all investigators.

Also undisputed . . . is the fact that the living matter composing all plants and animals consists of myriads of cells, all of which are able to perform the functions necessary for the nourishment, growth, repair and adaptation to environment of the vegetable or animal bodies which they compose.

Less general agreement, however, prevails regarding the capacity inherent in each cell which enables it to perform these vital functions and to regulate its actions so as to execute, or work out, what has been called its ‘blueprint’ or ‘template’—that is to say, the plan of its individual being. As we have seen, the ineluctable conclusion to which this inherent capacity of the cell leads us is that it has a psychological property, recognized by a number of authorities as ‘memory’, but which in final analysis is seen to be equivalent to intelligence. For, where memory prompts purposive action, we cannot deny it intelligence, and we are driven to a belief in the unexceptional association of all living matter with intelligence. Indeed, the two appear to be everywhere coextensive and indissoluble, and to infer a dualism from their coexistence can lead only to confusion and incoherence . . .

Thus, only can we understand purposeful adaptation, whether in plant or animal, as a process in which memory and intelligence cooperate, and when Dr Erasmus Darwin (in Botanical Garden, ‘Vegetable animation’, 1791) declared that, ‘The individuals of the vegetable world may be considered as inferior or less perfect animals’, he hinted at this idea. 143 years later, Sir J. Arthur Thomson merely echoed the doctor-poet when he said: ‘There is something of the animal in many a plant, and something of the plant in many an animal’ . . . The Venus flytrap, which quickly closes its toothed bilobed blade when an insect touches its sensitive hairs, abundantly confirms this claim . . .

The fundamental problems of adaptation to ambient conditions, variation and natural selection—or the survival of the fittest, as these processes occur in Nature to effect the evolutionary march of life—are insoluble if we approach them without always assuming some sort of intelligence in living matter, and here it seems to me that biologists like Darwin, Haeckel and their followers, and philosophers like Spencer, unnecessarily hampered themselves and invited the justifiable attack of lay thinkers like Nietzsche and Samuel Butler. Hence the justice of Professor McDougall’s description of Darwin’s theory of evolution as ‘a theory denying by implication all other agency and influence than the mechanical’ . . .

In the 1876 edition of Origin of Species Darwin said: ‘We are profoundly ignorant of the cause of each variation or individual difference’. Again, in the 1883 edition of The Descent of Man . . . he said: ‘With respect to the causes of variability, we are in all cases very ignorant’. This means that up to the moment of the actual appearance in any organism of features differentiating it, however slightly, from its ancestors, the Darwinian biologists know nothing concerning the history of such features. As Alfred Tylor observed: ‘The great difficulty in Mr Darwin’s works is the fact that he starts with variations ready-made, without trying as a rule to account for them, and then shows that if these varieties are beneficial the possessor has a better chance in the great struggle for existence, and the accumulation of such variations will give rise to a new species’ . . .

The earlier evolutionists did at least try to account for the origin of new features, and Lamarck . . . suggested a theory of their origin which, if true, implied the cooperation of the following important factors:

(a) A constructive and organizing power in the living organism, which in response to appropriate stimulation, even of an emotional or merely imaginative kind, could initiate structural changes and concentrations of energy, with corresponding modifications in the germ-plasm.(b) A capacity in the soma and germ-plasm to respond to such stimulation, provided always that it is given with adequate intensity and in strict accordance with the only conditions under which such stimulation can work . . .

Part 4 of 5

What, then, are the disconnected facts, the underlying relation of which would have vindicated Lamarck, shed important light on the evolutionary process and simultaneously explained many a problem connected with religion and religious practice?

What, then, are the disconnected facts, the underlying relation of which would have vindicated Lamarck, shed important light on the evolutionary process and simultaneously explained many a problem connected with religion and religious practice?

I suggest that they are, on the one hand, biological variation occurring under special circumstances, which we shall examine, and, on the other, those facts, positive knowledge of which has been recently acquired (although acted upon blindly for thousands of years), proving that it is possible for living organisms, and certainly for man (although perhaps less possible for him), to influence, and even to enlist the cooperation of, the formative, improvisatory and innovatory forces of living matter.

In other words, I suggest that it is now legitimate to postulate the feasibility of reaching and summoning to any activity whatsoever, and with any object (i.e., evil or benign), the hidden constructive and improvising forces operating incessantly in living matter, although these forces are normally inaccessible and unamenable to the conscious mental faculties of animals and man, and are in any case totally refractory in all circumstances to any volitional effort on the part of either beasts or human beings.

I intend to make a further claim, and to suggest that it is now probably consistent with acknowledged facts to say that we can reach and stimulate to any activity whatsoever (evil or benign) these same hidden forces even outside and beyond the range of our own living organism. It will, however, be noticed that in this connection I say ‘probably’, as I do not regard this claim as nearly so well-established as the former one. For the moment I shall be concerned only with the former claim.

It is common knowledge that for centuries mankind have been aware of their capacity, in certain not wholly conscious states, of contacting and summoning to activity powers in their bodies not normally under their control. In the East, among the religious devotees of Tibet and the yogis of Hindustan, and, nearer home, among the dervishes of Algiers, this has been a familiar fact for a much longer period than in Europe . . .

Now, apart from the successful use of hypnotism in surgery and midwifery . . . in the hypnotic state it appears to be possible to call into activity forces which, in the normal state, are quite inaccessible and cannot be mobilized. Nor should it ever be forgotten—as it always is forgotten, even by scientists when attempting to disparage parallels drawn between the relatively slight and superficial bodily phenomena induced under hypnotism and the deeper and relatively more elaborate phenomena of bodily change in living organisms, effected during the process of evolution—that the results obtained by hypnotism are all spontaneous, if not actually instantaneous, whilst Nature’s ultimate transformations, achieved by means of what Sir Julian Huxley calls ‘mainly small mutations’ . . . have unlimited time at their disposal.

How does an authority like McDougall describe the condition of the hypnotized subject? He says ‘increased suggestibility is its essential symptom’. That is true enough; but it is not enough, because, added to the increased suggestibility is the patient’s singular capacity to get into touch with the formative and usually inaccessible forces inherent in living matter, which in his unhypnotized state he is quite unaware of and incapable of mobilizing or of stirring to any activity whatsoever. We are therefore entitled to infer that, if the living organism is to be capable of activating the formative and improvisatory forces inherent in its cells, it is of paramount importance that its volition should be suspended and that only a suggestion of any desired effect should reach them. For the essential condition of the subject’s ability to activate the forces in question is his total surrender of his conscious mind, and above all of his volition, to the hypnotist; and, be it noted, not to the hypnotist’s will, as many assume, but only to his suggestions. If we lose sight of this crucial fact, we are unable to understand not only the phenomenon of hypnotism but many kindred phenomena which I shall now discuss, including some of the more fundamental aspects of religious practice . . .

We have but to read Charles Baudouin’s Suggestion and Auto-Suggestion . . . in which many impressive results of Coué’s method are recorded, in order to appreciate that not only in therapeutics but in every field of human endeavour, mental and physical, Coué’s technique for enlisting, or more properly invoking, the formative and improvisatory forces latent in living matter at once frees us from the cumbersome necessity of hypnotism and, what is even more important, provides us with the rationale of bodily changes brought about in states of suspended volition . . .

Sir Julian Huxley tells us that ‘it is mainly small mutations which are of importance in evolution’ . . . and . . . not only Lamarck but also other evolutionists, including Darwin, give us ample grounds for connecting variation with changes in environment . . .

On the other hand, persistence of type for as long as millions of years, as for instance in Amphioxus, Heterodontus and Sphenodon, in lung-fish and lamp-shells, and even in such mammals as opossums, hedgehogs, dogs, pigs and lemurs, points, as many biologists suppose, to a certain constancy in the circumstances of these creatures’ lives. Thus, Sir Julian tells us that ‘there has been no improvement in birds, regarded as machines for flying, for perhaps 20 million years, none in insects for more than 30’, both of which facts seem to indicate that the creatures concerned have during all these ages found little amiss in their mastery of their environment, and, since any such failing would indicate an environmental change sufficient to account for it, it seems probable that in one respect at least their conditions have been stable. ‘Some less advanced types of organization’, Sir Julian continues, ‘such as lung-fish and lamp-shells, have remained unchanged for 300 million years or more’ . . .

The facts seem to indicate that variation and mutation (I refer to the ‘small mutations’ important in evolution), far from being universal or inevitable, more probably represent the organism’s reaction to any change in the environment which disturbs an equilibrium previously established between it and its conditions. This appears the more likely when we learn from Professor J.B.S. Haldane that the ‘genes for a major character, say hair density, may be replaced rather rapidly in response to environmental change’ . . . for in this example we have a change which may be very adverse and dangerous for the organism, and the fact that the state of distress thus created provokes a rapid readjustment, of the kind described, lends colour to the view that variation and mutation are organic responses to any environmental change serious enough to destroy the harmony previously established between the organism and its milieu . . .

Thus, when we try to picture what takes place in the psychophysical system of living organisms, especially of those lower in the evolutionary scale than man, which are less intellectual and conscious than he is, when an environmental change provokes a readjustment, whether of bodily structure, behaviour or both, we must suppose that the effort or striving or desire, which Lamarck postulated as the factor initiating adaptive modifications, amounts to the organism’s confining its mental response to the new conditions, to a mute aspiration which, translated into human terms, would be expressed by no more than the words ‘Oh, help! If only I could get out of this’ or ‘Oh, mercy! If only those of my members concerned could deal with it’.

The efforts amount to a blind SOS in which the desired end is imagined and its accomplishment assumed as inevitable. In the organisms lower than man, no volition would accompany these mute aspirations, because will implies the conception either of some definite thing willed or some definite power that will can urge or impress.

The creatures lower than man, knowing of no means—not knowing, for instance, that fins may be changed into limbs—leave the means to Nature or the life-forces, and only imagine successful adaptation, not narrowly defined, lying ahead. They only ardently desire a happy consummation. The most they might do, as we shall see, is to picture themselves in imagination surmounting the difficulties the changed environment confronts them with. And as there is no limit to the power and resource of the life-forces, the most intricate and ingenious means of overcoming these difficulties are generally found. The fact that this is not always so is suggested by the evidence we have of the sudden extinction of certain animal species, as in the period between the Tertiary and the Eocene.

What creatures lower than man, however, never do is to doubt their success in ultimately overcoming an environmental change, because doubt presupposes some conception of the possibility, feasibility or probability of an individual modification, and that conception they cannot have. It is man’s intellect that here is prone to defeat his purpose, and Troward says quite correctly that ‘our intellect becomes the greatest hindrance to our success, for it only helps to increase our doubts’ . . .

Now, there is nothing mystical or magical in this intervention of the formative and improvisatory powers latent in living matter in order to produce the organic changes needed for a successful response to an environmental change. It is simply the slow operation in Nature of processes observed to occur spontaneously and, consequently, on a much less elaborate scale in human beings subjected to hypnotism or practising passive auto-suggestion. Nor do all human beings necessarily differ fundamentally from animals in the way they respond to environmental difficulties. Many, though a small minority probably, have retained the animal’s faculty of contacting and mobilizing the life forces directly by simply visualizing desired ends without any component of will or doubt . . .

It is, however, man’s fatal misfortune that all the immense advantages his consciousness affords him are heavily outweighed in most of his species by introducing into human desires and aspirations two factors absent from the animal’s more subconscious thought: doubt and volition. By jeopardizing his chances of seeing his aspirations realized, they lead to endless frustration and despair . . . Only in religion has man—instinctively, presumably—lighted upon the means for mitigating this twofold evil. But as we shall see, even in religion he has not wholly circumvented it.

We have but to think of what the result would be if a hypnotist, in suggesting to a subject that the cold key he is about to lay on her arm was really white-hot, added the proviso, ‘If it really is white-hot’ . . .

Whether we are entitled . . . to assume that the suggestions thrown out intensively by an ardently aspiring being can reach the life-forces outside our own selves; whether, that is to say, we may believe that we are able by suggestion to move, as it were, the cosmic life-forces to affect the course of our own or other people’s lives, is a question much more difficult to decide than that which has occupied us in the foregoing discussion. But if there is truth in telepathy, clairvoyance and in the alleged terrifying powers of primitive medicine-men and shamans to inflict curses upon people, it seems as if there must be means of moving the cosmic forces through suggestion to produce effects beyond ourselves. The data regarding the unfailing efficacy of medicine-men’s curses are certainly too well-authenticated to be lightly dismissed, and many scientists have already expressed their belief in telepathy . . .

Editor's Note:

In this final selection from Anthony Ludovici's last book Religion for Infidels, (London: Holborn, 1961), I have augmented John Day's selections in The Lost Philosopher: The Best of Anthony M. Ludovici, (Berkeley, Cal.: ETSF, 2003) with the concluding sections of the book. On Ludovici's account, prayer is essentially meditation that mobilizes the deep forces of nature, even when it takes the form of petition addressed to non-existent deities.* * *

[T]he fact in question is that, in all religions, it is not the peculiar features that differentiate them one from the other that constitute the more sound, more impregnable aspect of their character; it is not their peculiar creeds, dogmata, metaphysical and ethical systems, hopes and fears, nor are these peculiar features the part of them that is most immune to destructive analysis and criticism. On the contrary, these are the least sound, most perishable parts, the parts most deserving both of criticism and destructive analysis.On the other hand, it is that aspect of them which consists in the manner of their observance, their physical drill, so to speak, which by its uniformity, almost throughout the whole of the human world, unites and stamps them as castings from a common mould; it is this aspect of them alone which is sound, unassailable and indestructible, if not immutable. Thus, not what mankind have here and there believed, not how they have interpreted the nature of the power behind phenomena, has been the rock of ages found on immutable truth, but the way their divination led them to order the kinaesthetics of the ritual of their religion, no matter what its tenets might happen to be. Indeed, the creeds and dogmata of the various religions more often act as hindrances rather than as aids to a proper religious life. Certainly this is the case in England today . . .

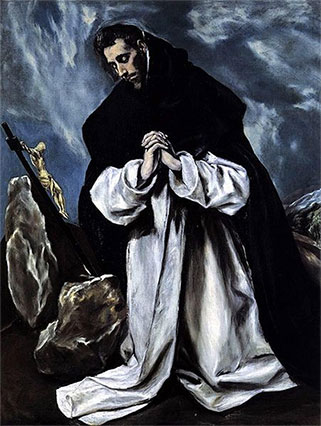

Thus, if in accordance with this conclusion, we study one of the most basic ritualistic features common to most religions—the posture of the religious man in the act of worship and supplication—we find a striking similarity between them. Whether we turn to Islam or Hinduism, to the ancient Hebraic religion or to Christianity—aye, even if we turn to the religion of the old Assyrian states—we invariably find that the posture assumed by the worshipper and petitioner is of a kind which psychologically spells self-surrender, the suspension of personal volition. In plain English, we find prostration, genuflexion or at least the sinking of the body and the bowing of the head as the posture of choice for the worshipper, especially in appealing as a supplicant to his godhead. The whole attitude is symbolical of the sentiment, ‘Not my will, but thine be done’ (Luke 22.42).

‘And at the evening of the sacrifice’, says Ezra, ‘I arose from my heaviness; and having rent my garment and my mantle, I fell upon my knees and spread out my hands unto the Lord my God’ (Ezra 9.5) . . .

It is always the same pattern. Genuflexion and the gathering of the body together in an attitude of will-less subjection . . . seems to be man’s natural reaction to the emotion accompanying self-surrender and humble supplication. Even among unsophisticated primitives this appears to be so, and in Christianity as early as St Basil (AD 330–379) kneeling was described as the lesser, and prostration as the greater, penance. Wherever the denial of any velleity to self-assertion, self-sufficiency or self-affirmation is the dominant mood, men almost universally and certainly instinctively fall into the posture instantly recognizable as expressing the abandonment of self-direction. Only when they praise or thank their deity do they stand, because in praise and thanksgiving they strike a personal note, express a personal appreciation and offer personal judgements for acceptance. Hence the posture during the recitation of the Psalms and in the singing of hymns.

It is, however, most important to bear in mind that the posture has not merely an objective significance. Even more vitally significant than its instinctive character and its impression on the onlooker is its subjective influence on the individual worshipper or supplicant himself, for its effect on his mind is to help him suspend volition. Apart from any emotions that may accompany it, qua poise it suggests to the mind of the supplicant the very mood or state most favourable to the success of his petition—namely, the abdication of his will. Indeed, it would be difficult to imagine a more ingeniously effective method of suspending will power than the assumption of the one posture in the whole repertory of human muscular adjustments—falling on the knees, the sinking of the body into relaxed folds from which all tenseness has been banished—which most persuasively eliminates will power . . .

Indeed, its very antiquity, its roots in the animal world of millions of years ago, causes it to be so unmistakable, so instinctive, that the sense of compulsion which forces men in religious supplication to fall on their knees and make all the muscular adjustments compatible with the suspension of volition is probably but a hang-over, a vigorous age-long and immortal vestige of that instinct in animals which, operating in response to an untoward environmental change, places them in imagination in touch with the life-forces and enables them to mobilize formative and improvisatory powers that secure improved adaptation . . .

The French are wont to say: ‘N’est pas diable qui veut’ [It isn’t the devil who wants.]. With equal accuracy it might be claimed that ‘N’est pas religieux qui veut’ [It isn’t the religious who wants.]. For it is not only a matter of keeping volition at bay. Prayer also depends for its efficacy on the amount of concentration, imaginative power and passionate desire we are capable of. In these democratic days we frivolously assume that everyone can love and feel deeply; we endow everybody with the gift of enduring attachment and the capacity to stay the course in passion. Similarly, we quite gratuitously assume that everyone can pray and perform those rites and exercises in contacting the life-forces which are akin to prayer and the results of which may be disclosed as either benign or evil.

Yet the increasing incidence of wrecked marriages, and the rapidly loosening hold that religion has on all modern people, never seem to awaken us to the gravity of our error in expecting of all our fellow-men and-women mastery in activities which depend above all on ardent sensibilities and enduring passion. Because in love, as in prayer, as also in the inflexible adherence to any direction or aim, it is character, depth, stamina and singleness of purpose that are fundamental, and what chiefly stamps our age is shallowness, languor, neurasthenia, weakness and more especially plural and conflicting impulses contending in the same human breast. For this reason, apart from the widespread ignorance of the technique of prayer and its kindred exercises, it is extremely rare to find anyone far removed from the rude forest vigour of primitive mankind who is able to love or to pray, since ordinary competence in either of these undertakings depends on much the same temperamental integrity and strength. Hence the difficulty a modern psychologist may feel in hiding his misgivings when any average young person today speaks of his or her love as of a phenomenon that will halt the stars in their courses.

It is facts of this nature that are too often, if not habitually, left out of the account in estimating the efficacy of the various means of approaching and mobilizing the life-forces, and in the pronouncement of imprecations and curses. Yet, unless we allow for the factor of personality and the endowments of the individual man or woman who prays or employs some occult means of influencing the life-forces, how can we assess the efficacy of the means used? To condemn them offhand as myths or as ineffective without first scrutinizing their users would be as foolish as to disparage a 12-bore gun because it had made no kill, before we ascertained the marksmanship of its user. It is all the more important to be cautious in this respect, seeing that we live in an age in which debility, nervous prostration, general constitutional inferiority and instability of character are common to all classes of the community, and that consequently the qualities demanded of a good lover and of a competent man of religion have hardly ever been so scarce as they are today in modern northwestern Europe . . . (Religion for Infidels, pp. 146–254)

* * *

What, then, is a reasonable conclusion to draw from all these findings? How is the infidel to understand and practise his religion?

First of all, he must try to grasp the nature of the life forces and the way they work; and, in order to do this, he will have to rid his mind of many deeply rooted, age-long assumptions about both the power behind phenomena, Man and the Universe. This may be his most difficult task because the philosophical and religious traditions of Europe are based upon these assumptions, and the thought and behaviour they inspire have become largely instinctive in the white man. It is, however, hoped that this book, elementary and imperfect though it may be, will offer him some help and guidance in the undertaking. Above all, he must accustom himeslf to the idea that the life forces, being utterly destitute of anything remotely resembling morality, the suggestions made to them in prayer, are accepted whether they happen to be good or evil. This is a truth towards which the Christian scientists have long been tending, though without any logical grounds in their cosmology, when they assert that illness and all other untoward turns of fate are due to “wrong thinking”.

Secondly, he must apply himself to acquiring a mastery of the technique of prayer; an accomplishment which, as we have seen, is far from easy, and far indeed from being purely psychological. As Wordsworth so truly said, “to converse with heaven — this is not easy” (The Excursion, Book 4). Only with the appropriate co operation of his body can he hope to attain to any mastery in this essentially religious practice. This truism, which sounds platitudinous in the ears of one who has long given up the absurdity of dualism, has to be repeated ad nauseam, because, imbedded in European tradition, its flat contradiction has reigned undisputedly for close on two millenniums.Thus, in a book recently published — Prayer Can Change Your Life, by Dr. W. R. Parker and Elaine St. Johns, 1959 — with the principal claim of which I agree, there is no mention of the necessary kinaesthetic (the physical or bodily) component of prayer, if it is to be effective. The authors’ nearest approach to the matter is to stress, quite properly of course, as they do on pp. 135, 136 and 159, that prayer is “an act of surrender”. How much more valuable their book would have been had they tried to state precisely how the body must co-operate if the surrender is to be perfect.

Enough has been said on this subject to make it clear that even to differentiate the psychological from the physical components of any human action or activity, in itself reveals an outmoded, not to say exploded, point of view. There can be no psychological exercise whatsoever, in which the body does not co-operate, and this is nowhere more true than in the activity we call prayer. Unless the recueillement of the spirit finds its parallel, confirmation and support in the appropriate bodily adjustments, the mood and temper indispensable to the proper performance of prayer cannot be summoned. Hence the absurdity of supposing, as many religious bodies do, that religion is wholly a matter of the “soul” or spirit.

For we have accepted Professor William James’s view that “Prayer is religion in act, that is, prayer is real religion. . . . Religion is nothing if it be not the vital act by which the entire mind seeks to save itself by clinging to the principle from which it draws its life” (V.R.E. Lect. XIX). We have also agreed with the Rev. Edwyn Bevan, that “prayer is by the very definition of the term petitionary . . . asking that something we desire [innocent or malefic] may take place” (C.P. Chap. VI). Unless, therefore, we know how to pray, we cannot pretend to be religious.

Strange as it may seem, even the question of whom we address when we pray, is of less fundamental importance than the manner of our supplication; because even when a man’s cosmology, like that of the Christian, is palpably false and self-contradictory, the fact that he may know how to pray will inevitably mean that the life forces will be stirred; although, when he recites his prayer, his lips and tongue will pronounce the words, “Father, Son and Holy Ghost.”

So that when we say prayer and the knowledge of how to perform it, are the whole of the infidel’s religion, we are excluding no essential factor of the religious life, nor do we differ from Professor William James and the Rev. Edwyn Bevan in any respect, except the important one of the cosmology we hold to be consistent with the scientific and philosophic conclusions of our age.

Thirdly, the infidel aspiring to a religious life, should bear in mind a truth not easy to accept in these days of reckless and fanatical democratization. At a time when standardization prevails in every department of human life, except where it is most important and most urgently needed — i.e., in the sphere of somatotypes, so that, although mass propaganda infects all of us with the same degenerate values, we are all so disparate, one from the other, that to see a thousand modern English people randomly collected together, is to behold as many distinct, incompatible and conflicting constitutional types — at such a time as this, when we are all egalitarians and resent having to concede any fundamental qualitative distinction, except the financial one (and even that is not true of everyone), between men, it is painful to be told that all are not equally endowed, whether for sound judgment, love, or prayer. We listen without indignation, let alone nausea, to thrice-married divorcees, male or female, when they declare that a new “passionate” attachment has swept them off their feet; just as we hear without incredulity of the hurricane engagement, marriage and honeymoon of one whose lack of stamina and fire might have allowed him to temporize with his passions without inconvenience through three lifetimes. In spite of massive evidence to the contrary, we in fact assume that everybody can love”. Nor, when we see the average congregation filing out of church or chapel after one of their so-called “bright” services, does it ever occur to us to speculate on the proportion among them of people who have been truly capable of any religious observance, let alone prayer.

But unless we courageously try to know ourselves and have the nobility of character uprightly to recognize and resign ourselves to our particular limitations and deficiencies; unless we profit from the lessons of our life in order to assess approximately the sum and nature of our endowments, we may be bitterly disillusioned when we embark on any enterprise which depends on passionate earnestness and ardent sensibilities for its happy consummation. I repeat, “N’est pas amoureux ni religieux qui veut.” It is, therefore, inaccurate and actually uncharitable to lead everybody to believe that he is capable of love or religion; and such forms of deception can end only in frustration and misery.

To assume, as most modern people do, that without the requisite natural disposition and, above all, without any preparation in the psycho physical technique of prayer, any man can at the drop of a hat become a convert — an assumption at least implicit in the sort of mass religious enlistment of a recruiting missionary like “Billy” Graham — reveals not merely a profound misunderstanding of the subject, but also a shallow underestimation of its gravity and importance. Even the recruiting departments of the Army and Navy are wiser than this; for their present high proportion of prompt rejections, despite the relatively low standard of their requirements, which in any case are inferior to those that might reasonably be expected of a religious recruit, shows how far they are from assuming that psycho-physical fitness for the Services is a universal attribute.

It would, therefore, be most interesting to know how many rejections per cent the Salvation Army, for instance, has to make every year from the number of its recruits. Aware as I am of the slap-dash methods of religious recruiting in general, I should guess, none. Even to suppose that everybody, when once given the necessary information and training in the technique, can become capable of, or can reach more than an amateur standard in religious observance is, as we have seen, a sad illusion. The most that might be conceded is perhaps that, as a desperate clinging to life is common to all men, there may be a moment in all human lives, irrespective of individual constitutional differences, when, if mortal danger threatens, passionate desire, like the temperature of one gravely sick, may soar to such abnormal heights as to simulate the native ardour of the gifted lover or man of religion. But, what may jeopardize even this means of performing efficacious prayer, is the fact that, in such ecstatic paroxysms, generated by deadly peril, passionate longing easily swings in the direction of importunate solicitation, peremptory imploration; in which case, as we know, volition stealthily intervenes and the effect is nugatory.

Does this mean that all hope, all chance, all prospect of leading a religious life should be denied to the majority of mankind? Not in the least! It is simply a timely and solemn warning, stated with perhaps exaggerated emphasis, because it is too seldom stated, that as the efficacy of prayer is no myth, no romantic fancy, or idle hoax, if it is found to fail, the fault should be sought, not in prayer, but in him who prays.

There remain one or two matters so far unsettled, and foremost among them is the question whether the infidel may include in his religious credo a belief in life after death.

All that can at present be said in reply to this question is that there is absolutely no evidence pointing to immortality, least of all for what is mystically called the “soul” of man. The whole idea of immortality as modern people conceive it — i.e., restricted to the soul alone — is moreover based upon a dichotomy for which, as we have seen, there is so little foundation either in the data of science or in the rules of reason that, except for the fact that it satisfies a natural craving, there is little to be said for it. Truth to tell, the position regarding this idea has altered so little since the middle of the eighteenth century, that, throughout the whole course of the last two hundred years, the validity of the conclusions reached by Hume in his essay, On the Immortality of the Soul, may be said to have remained unshaken.

As early as the fourth century A.D., from the prevailing thought of which our Apostles’ Creed derives, it is evident that Christian philosophers were then doubtless still unconsciously swayed by the realism and superior logicality of antiquity; for in that Creed all churchmen in their Morning Prayer proclaim their belief in the “resurrection of the body” (or the “flesh” as the old version had it), a belief which, however fantastic it may also seem, is nevertheless considerably more rational than the idea of a disembodied ghost living, not only eternally, but also blissfully. It may be that, in this notion of soul immortality alone, we have a reverberation of that Socratic and puritannical contempt of the body which, as we have seen, is probably the root of the dualistic concept, “body-soul”, as championed at least by Socrates (for it has older roots in Animism).

Be this as it may, it reflects but little credit on us of a generation so much later than that of the fourth century, that we should be able to regard the idea of the resurrection of the body, except for the lip service we may pay it when reciting the Apostles’ Creed, as less acceptable than the notion of the immortality of the soul. And this is one of the few instances in which Christian dogma, owing to its tincture of ancient wisdom, reveals itself as more enlightened than modern thought. Although the belief in either consummation calls for some goodwill and forbearance on the part of an intelligent mind, and is an indication of the absurd lengths to which men will go in unreason and fantasy in order, as Hume points out, to gratify their longing for permanent survival of some kind, one needs to be possessed of excessive naïveté, not to say gullibility, in order with any sincerity to be able to entertain a belief in a heavenly society of countless billions of spectres, spooks and wraiths, revelling in an eternal existence.

Another religious matter to which the infidel may expect reference to be made, is the question whether the power behind phenomena is a person. Troward claims that it is impersonal. My own view is that we have insufficient evidence to decide this question either way, and our present knowledge does not warrant any final decision about it. Behind the life forces there may be what we understand as a personality; but we do not know and cannot tell. All that we can positively state, and with the most complete conviction, is that if there is such a divinity or supernatural person, he cannot bear the faintest resemblance to the Jehovah-God-Father-Creator-First-Cause concept of the Christian cosmology. On the contrary, we could probably not hope to get a more exact image of his being and character than by flatly contradicting everything Christianity alleges about him, except his omnipotence, and by writing against every item in the Christian catalogue of his attributes, the precise converse of what the Church maintains.

Finally, there remains the question of the morality that is compatible with the infidel’s religion, as it has been briefly outlined in these pages. What is there to be said about this? Here again, we have not only to rid our minds of most of the Christian moral precepts, but also to root out of our unconscious and spontaneous moral impulses, those which are the outcome of two thousand years of Christian indoctrination. We have to try to resist the overpowering influence of the tradition and the present-day moral climate of Europe, and particularly of England, in its blind insistence on the paramount desirability and moral value of unselfishness and unselfish behaviour.

Based as this insistence is on an utterly false psychology, we have to re-learn Nature’s way, which teaches us that only those actions and that behaviour are clean, wholesome, fragrant and founded on genuine sentiments, that are performed selfishly, and that we are therefore wise to eschew all those situations and relationships which are likely to demand the protracted exercise of self abnegation or denial. We must awaken to the fact that the moment any need for unselfishness insinuates itself into a situation, that situation is morbid and faulty. We must accustom ourselves to the thought that to have to behave unselfishly is already to have progressed some way along the wrong road, whether domestically or socially, and that every human relationship calling for so-called “altruism”, is on the rocks.

We must learn to regard pity as virtuous and admirable only when it is extended to the promising and desirable. Directed anywhere else, it is morbid and a sign of sentimental self-indulgence.

In our practice of charity, we should try to remember Nietzsche’s dictum to the effect that it is innocent posterity that usually has to pay for that love of our neighbour which Christianity enjoins. All about us today, as even the blindest must recognize, are proofs that we are all members of a posterity cruelly, crushingly penalized by the exorbitant neighbour-love displayed by our fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers. They had their voluptuous fling in indiscriminate full-throated pity and reckless benevolence, and we, the victims of it are now paying in treasure, depression of spirits, oppression, and every kind of shackle on the flourishing life of our Age, for their “virtuous” self indulgence and their hope of heaven.

We must abandon the nonsensical view that love can be voluntary — a view implied by the Christian belief that it can be commanded or summoned by will. It has wrought so much harm and still causes so much bitterness in the world, that we cannot too soon nail it as counterfeit to the counter of commendable conduct.

Nevertheless, doubtless owing to the few intellectual pearls it happened to pick up during its early contact with pagan antiquity, the Christian Church sometimes reveals much greater wisdom than modern European and English thought. I have already given one instance of this. Another is its attitude towards the question of man’s pristine moral character. Contrary to the sentimental, erroneous and relatively recent view, championed particularly by Rousseau and nineteenth-century romantics à la Wordsworth, the Christian Church, with a realism exceptional in its Weltanschauung, and actually at variance with the view of its Founder (see Chap. III ante), has always maintained that man is born evil and has to become good, or fit for decent society, only by the action of external influences (“grace”). modern psychology has wholly confirmed this view, although thinkers like Dr. Johnson, Browning, Spencer and Baudelaire, as we have seen, long ago anticipated the recent scientific attitude to the question.

In any case it must be clear that, if we accept Jesus’s and Wordsworth’s point of view about children — i.e., to the effect that they arrive innocent, harmless and trailing clouds of glory “from God who is our home”; if we agree that “Heaven lies about us in our infancy”, the implication is that man is born good and that only his environment, the society into which he is plunged, subsequently corrupts him.

Now this point of view has been the source of an enormous amount of harm, especially in feministic societies like England and America; because, besides giving us a false picture of man’s primitive nature and innate tendencies, by making children appear sancrosanct and at all events morally superior to adults, it subverts the authority of their seniors, undermines discipline, and lends support to every mother’s self-indulgent urge to spoil her child, rather than to train it to become a fit member of a civilized community. Nor can there be any doubt that the sensational increase in juvenile crime in recent years, especially in England and America, has to a very great extent been due to this one feature in the body of false doctrine that now rules over modern public opinion.

The wise and thoughtful infidel will therefore incline in his morals to the point of view of the Christian Church, rather than to that of Jesus and the Wordsworthian romantics. He will hold the sensible view, now established by scientific psychology, that children are more asocial, more evil, than their seniors, that only when they have been purged of their asocial impulses and appetites can they be regarded as “good” or fit for their place in the community, and, therefore, that man cannot be regarded as born good.

To conclude this brief sketch of a morality to suit the infidel’s religion, we may summarize the whole of the duties of man in society as having for their object under all circumstances to promote and defend all those influences and points of view which favour superior and flourishing, and to resist and condemn all those influences and points of view which favour decadent and degenerate, human life. Everything eke denotes a misunderstanding of the proper function of compassion and is a crime against both justice, sanity, good taste and — posterity.

* * *

This, then, concludes the description of the religion for infidels. In view of the harmony of many of its features and of its methods of contacting and of turning to its own account the formative and improvisatory powers of the life forces, it might perhaps be properly termed a “natural” religion; except that, in its observance by humanity, there is a provision in the moral code consistent with its cosmology, that amounts to an unnatural factor, or a factor not found operative in Nature (except possibly precariously, as we have seen, in the influence, of the will to power). For in the above-mentioned summary of the duties of man in society, we have seen that there is a strong influence that should operate constantly against degenerative trends, whereas in Nature, there is no similar influence, and degeneracy is just as likely as regeneracy to supervene.

In this respect, provided that mankind should faithfully observe the duties above mentioned and abide by the code as summarized at the conclusion of my sketch of the morality, the religion for infidels is really superior to that of a truly natural religion; although, as we have no guarantee whatsoever that the moral code as summarized above will necessarily be observed by the majority of mankind, this superiority is far from being a certainty. The chances that the degenerative trends in Nature herself may not be consistently resisted and overcome by humanity, must therefore remain a possibility. Indeed, the evidence at present is all against a belief in the ultimate victory of the more desirable tendency. But this should not deter us from doing our utmost to promote this tendency and from furthering all those schemes and policies which aim at ensuring its ultimate triumph.

http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/02/religion-for-infidels-part-1/#more-45505