NIETZSCHE AND THE ORIGINS OF CHRISTIANITY

Thomas Dalton

Over the course of two thousand years, Christianity has grown from nothing to the largest religion on the planet. Some 2.1 billion people now consider themselves Christian, about one third of all of humanity. It significantly outnumbers Islam, in second place with 1.5 billion members.1 America is among the most religious of all industrialized nations; about 77 percent are Christians, and most of these are regular church-goers. And yet few people, even Christians themselves, understand the origin of this most influential religion. In one sense, we will never truly understand exactly what events transpired two millennia ago, in that land of shepherds, nomads, and dusty villages of the near Middle East. Archeology tells us some things, ancient documents others. But these give us only an outline of the facts of that place and time. If we wish to comprehend early Christianity and its implications for today, many gaps must be filled in—by analysis, probability, guesswork, and faith.

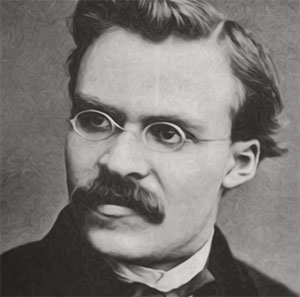

Friedrich Nietzsche took a great interest in Christianity and its allied religion, Judaism.2 This interest was strikingly—shockingly—negative. The title of his final book, Antichrist, gives a good indication. For Nietzsche, Christianity was decadent, weak, and nihilistic. It led to a sickly, subservient herd morality and suffocated the quest for human excellence. Worst of all, it replaced a life-affirming naturalness with an otherworldly, life-denying negativism. It has become, in fact, “the greatest misfortune of mankind so far” (Antichrist, sec. 51).3 This disaster of Christianity is impossible to understand, he said, without grasping its Jewish roots. Thus it is not simply Christianity, but Judeo-Christianity, that must be examined with brutal honesty, if we are to overcome its weaknesses.

Before looking in detail at Nietzsche’s critique, I want to review the state of knowledge on the origins of this religion. We know much more today than Nietzsche did in the late 1800s. But it is to his credit that the present facts seem, by and large, to bear out his analysis—though perhaps his conclusions remain as controversial as ever.

Historical Background

Consider, first of all, the ancient origins of Judaism and the corresponding events of the Old Testament (OT). The original patriarch, Abraham, apparently lived some time between 1800 and 1500 bc — he being the traditional father of not only Judaism (and thus Christianity) but a leading prophet of Islam as well.4The next major figure, Moses, lived around 1300 bc, and some time afterward the “Five Books of Moses” began to take shape, likely at first as an oral tradition. These books would eventually form the Pentateuch (Torah) — the beginning of the OT.5

The remaining 30-odd OT books were added over the next one thousand years, the set becoming complete around 200 bc. These books were written in Hebrew, but a Greek translation — the Septuagint — was begun about this time, completed circa 50 bc. The Dead Seas Scrolls, which date to the first century bc, contain fragments from every book of the Hebrew OT, and thus are our earliest proof that the complete document existed by that time. Whether it appeared any earlier is a matter of pure speculation.

Dating of the OT texts is one thing; accuracy is another matter. The earliest dates cited above are conjectural, since we have no recorded reference to the travails of Moses prior to 850 bc. Furthermore, prominent Israeli archeologist Ze’ev Herzog has shown the increasing discrepancies between archeological data and the biblical stories.6 Efforts in the 1900s to confirm the OT yielded a plentitude of new information, but this “began to undermine the historical credibility of the biblical descriptions instead of reinforcing them.” Scholars were confronted with “an increasingly large number of anomalies,” among these: “no evidence has been unearthed that can sustain the chronology” of the Patriarchal age; the Exodus, “the many Egyptian documents that we have make no mention of the Israelites’ presence in Egypt, and are also silent about the events of the Exodus”;7 and the alleged conquest of Canaan (Palestine) by the Israelites in the 1200s bc is refuted by archeological digs at Jericho and Ai that found no existing cities at that time.

Even the famed monotheism of the early Jews is undermined by inscriptions from the 700s bc that refer to a pair of gods, “Yahweh and his consort, Asherah.” An overall picture comes into view: a kernel of true people and events magnified over time, acquiring legend status. Disparate tribes of wandering and warring Jews become heroic freedom fighters, and ultimately the chosen people of the (eventually) one God.

Nietzsche appreciated the Old Testament—in spite of his skepticism about its historical veracity. He liked the power of the language and the concept of a ‘God of the Jews’, a god appropriate for a given people and a given time, one who rewarded and punished in equal measures. “In the Jewish ‘Old Testament,’ the book of divine justice, there are human beings, things, and speeches in so grand a style that Greek and Indian literature have nothing to compare with it” (Beyond Good and Evil, sec. 52); and again: “all honor to the Old Testament!” (Genealogy of Morals, 3.22).

The New [Christian] Testament — was a completely different matter. Again, the historical facts set the stage.

The Maccabean revolt of 165 bc, against the Seleucid Empire, reestablished Jewish rule over Palestine. The resulting Hasmonean dynasty was formed in 141 and ruled until the Roman Empire incorporated the region in 63 bc. Until that time the indigenous Jews had lived under many occupying powers — Persians, Babylonians, Alexander the Great — but apparently were able to accommodate their foreign rulers and still thrive.

Things were different under the Romans. Having been the ruling power in Palestine for 100 years, the Jews were dismissively subsumed into the Empire. Governance became increasingly callous and brutal. In addition to passing judgment on Jesus, Pontius Pilate was known for his aggressive treatment of the Jews; things grew worse after his removal in 36 AD and the ascension of Emperor Caligula. Ben-Sasson writes, “The reign of Caligula (37–41 ad) witnessed the first open break between the Jews and the Empire. … Relations deteriorated seriously.”8 Tensions culminated in the first Jewish revolt, begun in 66 and ended in Roman victory and the plundering and destruction of the Jewish temple at Jerusalem (Herod’s Temple) in the year 70 — which had stood in place since 516 bc.9

Rome retained power over Palestine for nearly 400 years, until the fracturing of the Empire in 395. The surviving Eastern (Byzantine) Empire continued to rule the region for another 240 years, until the Arab Caliphates took over in 638. Thus it is clear that Roman rule, beginning in 63 bc, was decisive for the emergence of Christianity. Nietzsche seems to have been the first scholar to grasp the significance of this fact: “Without the Roman Caesars and Roman society, the insanity of Christianity would never have come to rule” (Will to Power, sec. 874).

Nietzsche’s Analysis of Christianity

How shall we understand Christianity? Nietzsche’s analysis starts from three essential facts. “The first thing to be remembered if we do not wish to lose the scent here, is, that we are among Jews” (sec. 44). This much is obvious, but it bears repeating. Jesus was a Jew, as were his parents Joseph and Mary and all 12 apostles. The three other main figures of the New Testament—Mark, Luke, and Paul—though not apostles, were also Jews. And the many unknown authors that contributed to the New Testament (NT) were almost certainly Jewish as well. This is not incidental and not a question of individual character or action; “[it is] a matter of race.”

Not just Jews, but lowly Jews—the ‘chandalas’, as Nietzsche calls them, the untouchables, the lumpenproletariat: “the people at the bottom, the outcasts and ‘sinners’, the chandalas within Judaism” (sec. 27). It was these men that gave birth to this great religion of redemption.10 Even granting that Nietzsche exaggerates, it is clear that they were the low class, ‘blue collar’ people of the day — the farmers, fishermen, carpenters, and laborers. Christianity was born not simply of Jews, but of the lowest caste of Jews.

This is important to grasp because it demonstrates that the proto-Christian Jews had, in effect, two sets of masters: the Romans and their own elite Jewish priests, the Pharisees. They were doubly enslaved. In order to establish any sense of freedom and autonomy they would have to rebel against both parties—even as the Pharisees would be their allies against Rome. A difficult situation.

His second fact—an unquestioned assumption—is that the entire concept of an actually-existing, transcendent, all-powerful God is nonsense. Stories about holy visions, miracles, redemption, and divine intervention are nothing more than “foeda superstitio”—vulgar superstition. This does not mean Nietzsche was opposed to ‘God’ in principle. He believed that every people and every culture need to create their own concept of religion and of the divine. These things are a formalized recognition of respect and reverence toward that which embodies one’s highest values. Each culture and each era needs to create its god(s) anew, appropriate to their situation in the world. Western Europeans have utterly failed in this task:

There is no excuse whatever for their failure to dispose of such a sickly and senile product of decadence [as the Christian God]. But a curse lies upon them for this failure: they have absorbed sickness, old age, and contradiction into all their instincts — and since then they have not created another god. Almost two thousand years — and not one new god! (sec. 19)

A proper re-conception of religion, however, must be a truly uplifting, life-affirming, and ennobling enterprise — decidedly unlike Judeo-Christianity — and must never be taken as permanent and absolute truth. All superstitious, i.e. anti-natural, religions are out of the question. The human condition, and human ‘salvation,’ must be firmly rooted in the present, physical world — the real world.

The third basic fact, as explained above, is the historical context of the Roman occupation and persecution. Without this, the events of the Christian era are incomprehensible.

* * * * *

With this in place, let me attempt to reconstruct Nietzsche’s conception of early Christianity. This is difficult in any case, due to the radically unsystematic nature of his writing. But a coherent picture emerges from his many disparate observations.

In Nietzsche’s view, Jesus was a humble Jew, an ordinary man, though clearly a leader and moral preacher of some merit. He spoke of the value of humility and pity, and of a God who viewed with compassion even the lowliest slave. Jesus sought to relieve suffering through compassion — the ‘Kingdom of God’ within each person. Simultaneously he opposed, via a path of nonviolent resistance, both the social oppression of the Pharisees and the political oppression of the Romans. To achieve all this, it was necessary to “spread the word,” the Good Word of God. Jesus’ life, his faith, and the faith of the real Christian were essentially pragmatic. His faith was the response of a lowly Jew struggling to assist other lowly Jews in the face of oppression. Thus follows the practice of true Christianity, which is its essence:

Christianity projects itself into a new practice, the genuine evangelical practice. It is not a ‘faith’ that distinguishes the Christian: the Christian acts, he is distinguished by acting differently: by not resisting, either in words or in his heart, those who treat him ill… The life of the Redeemer was nothing other than this practice — nor was his death anything else. … Only the evangelical practice leads to God, indeed, it is ‘God’! (sec. 33)

This was absolutely appropriate for a man in Jesus’ situation—an underclass Jew fighting oppression and seeking to help his fellow sufferers. But this was a specific situation, appropriate only to a particular time, place and culture. In a real sense Jesus was, and could be, the only ‘true’ Christian: “in truth, there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross. The ‘evangel’ died on the cross” (sec. 39). But to exploit this singular example, to universalize it, to use it as a generalized weapon against the powerful and noble classes, against nature and against life itself — this was the crime, not of Jesus’ doing—though he too was a ‘criminal’—but that of his followers; first and foremost, Paul.

The ground was ripe for exploitation in that first century of the new millennium. Traditionally the Jews had a long history of prophesies of coming saviors, of redeemers, and of a messiah who would deliver them from suffering and slavery, and restore the Kingdom of Israel as it was in the era of the so-called unified kingdom of David in 1000 BC. But for all this talk of saviors, there is surprisingly little textual basis in the OT. The Pentateuch contains no mention of a messiah. Neither do the ‘historical’ or ‘poetic’ books. Only the prophets speak of a savior, rarely and obscurely; nearly all references of any specificity are found in just one book—Isaiah. In any case there was some extant tradition for such a man, and if there ever was a need for him it was during the Roman occupation.

There is strikingly little evidence that, during his lifetime, people considered Jesus to be ‘the’ Messiah. He was born around 4 BC, but we have astonishingly few details of his early life—apart from the miraculous virgin birth described in the Gospels, which are problematic in themselves. It has struck more than one commentator as extremely odd that this miracle child could be born and then all but drop out of sight for some 20 or 30 years.11 Virtually nothing is known about the facts of Mary’s life, and even less of Joseph; even the years and places of their deaths are a mystery.

Surprisingly, there is virtually no recorded documentation about Jesus during his lifetime by anyone who personally knew him. Jesus himself wrote nothing, which, while not impossible, is counter to a long tradition of moral or spiritual teachers leaving a written legacy. (if he was in fact a poor uneducated Jew, he likely did not know how to write.) In spite of alleged miracles performed in front of thousands of people—recall the fishes and loaves story— no one at the time bothered to record such momentous events on paper. The men who knew him best, the 12 apostles, wrote nothing.12 Of their lives we know almost nothing, other than some presumed years of death for five of them (John, Peter, Phillip, Thomas, and Judas). Again this is striking; once the true nature of the Messiah was confirmed by his resurrection, one would expect his followers to be revered themselves, their every step noted and recorded.

At this point the student of the Bible will respond that two of the apostles, John and Matthew, wrote their corresponding Gospels. But few experts believe this today. The present consensus is that the four Gospel authors were anonymous individuals who did not personally know Jesus.13 Based on events mentioned in them, however, scholars have assigned them approximate dates. The earliest was Mark, written about the year 70, some 40 years after the crucifixion. Again, this is an amazingly long time to wait to record the miracle of the Messiah, even if done by Mark himself (a man who did not personally know him).

Nor do we have any confirmation of Jesus’ life story from contemporaneous non-Christian sources. One would certainly have expected his enemies to document his life, if he had been a person of substance or threat. But no such writings exist. The earliest mention is by the Jewish author Flavius Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews from circa 93 AD. Pliny the Younger and Tacitus both refer to the Christians in their writings of the early 100s AD. Again, these sources come 60 to 70 years after Jesus’ death — not what one would expect.

By all accounts, then, Jesus was a rather ordinary individual, a preacher of faith and action, and a consoler of troubled souls. He likely counseled his fellow down-trodden Jews to stick up for themselves, and perhaps to disobey the unjust Roman rule, and even the contemptuous dictates of their own Jewish elite. Such rabble-rousers were frequently exiled or put to death (recall Socrates), and so it is not surprising that the elite Jews would agitate for his execution — against the reluctant wishes of Pilate himself, if in fact he was ever truly involved. We know the result: “God on the Cross.”

Then we come to Paul. For Nietzsche, as for many other scholars, Paul is the central figure in early Christianity — to the extent that ‘Paulism’ would be the more appropriate designation. In Paul’s rendering, Jesus — the real Jesus — becomes virtually irrelevant, even counterproductive. Paul needed not Jesus’ life, but his death; only this could work miracles. The entire story of Jesus’ life was rewritten and altered, motivated not out of love but the very opposite: feelings of hatred and revenge toward the conquerors:

In Paul was embodied the opposite type to that of [Christ]: the genius in hatred, in the vision of hatred, in the inexorable logic of hatred. … The life, the example, the doctrine, the death — nothing remained once this hate-inspired counterfeiter realized what alone he could use. Not the reality, not the historical truth! And once more the priestly instinct of the Jew committed the same great crime against history — he invented his own history of earliest Christianity.

The Savior type, the doctrine, the practice, the death, the meaning of death, even what came after death — nothing remained untouched, nothing remained even similar to the reality. Paul simply transposed the center of gravity of the whole existence after this existence — in the lie of the ‘resurrected’ Jesus. At bottom, he had no use at all for the life of the Savior — he needed the death on the cross and a little more. Paul wanted the end, consequently he also wanted the means. What he himself did not believe, those among whom he threw his doctrine believed. His need was for power; in Paul, the priest wanted power once again; he could use only concepts, doctrines, symbols with which one tyrannizes masses and forms herds. (sec. 42)

The real Jesus was thus reduced to a caricature, a trigger for some fictionalized grand narrative: “The founder of a religion can be insignificant — a match, no more!” (Will to Power, sec. 178). In Nietzsche’s view, then, Paul repeated the trick of the Old Testament: He took the basic elements of a man’s life and history, a kernel of truth, and wove out of this a fantastic story of miracles, immortality, and divinity incarnate. And precisely here was the source of the problem.

Recall the basic facts of Paul’s life. He was born in Tarsus (modern-day Turkey) around the year 10 AD as ‘Saul’, a Jew like the rest, though different in one important respect: He was not a chandala Jew, but rather a Pharisee, an elite Jew.14 He never knew Jesus, and was, in fact, an early and harsh critic of the Christians, he tells us. Then on his travels to Damascus in the year 33, three years after the crucifixion, Saul encounters the ‘risen Christ’ in a revelatory vision and is immediately converted. Taking the name Paul, he becomes the foremost champion of Christianity, even more so, strangely, than any of the apostles who knew Jesus. He begins to create fledgling churches around the Mediterranean, and in the process writes a series of letters — the 13 “Pauline” epistles — encouraging and cajoling his recruits, and declaring his faith in Jesus the Messiah. These epistles, by far the earliest written Christian documents, ultimately comprise nearly half the 27 books of the New Testament.15

Like his Savior, Paul evidently acquired a reputation as a troublemaker. He was arrested and sent to Rome for trial, though we know few details. He was apparently executed, either by beheading or crucifixion, some time in the mid-60s AD.16

Nietzsche is rightly suspicious of Paul’s conversion, and not only on grounds of ‘superstition.’ First of all, the two earliest epistles, Galatians and 1 Thessalonians, date to around 50 AD; this is a full 20 years after the crucifixion, and nearly as long after Paul’s conversion. Granted, starting up a new religion is slow work, but one would expect some written record sooner than this, particularly from an elite, well-educated Jew. Second, Paul’s conversion in or around the year 33 is virtually coincident with the initial outbreak of Jewish-Roman antipathy — during Pilate’s reign, and just prior to the major break in relations attributed to Caligula. This suggests some causal link. Third, things worsened under the subsequent emperor, Claudius, as he expelled the Jews from Rome in the year 49 (see Acts 18:2), just about the time of the first epistles. Fourth, the epistles are strikingly lacking in details about Jesus’ life: nothing on his birth, early life, ministry, or the apostles. This suggests that Paul either did not know, or did not care, about such trivial details.

Part 2

But Nietzsche's main contention, and his most controversial conjecture, was this: Christianity as Jewish revenge. He paints the following picture, to which I have added factual details as we understand them today.

Paul could see the growing oppression of the Jews. They had only limited ability to fight back militarily. They were increasingly frustrated and trapped, confronted by a larger and more powerful enemy than they had ever encountered before. So Paul, perhaps together with Luke, Mark (both educated, upper-class Jews) and Peter (the chandala apostle), concocted a plan. They could not use force against the Romans because the Jews were too few and too weak. The Romans were also few in number, and militarily strong. But the common man, the masses, especially the chandala Gentiles — they were many. If they could come to oppose the Romans then an overthrow, a revolution, might be possible; or at the very least, the iron-grip rule would be weakened. But the Gentiles did not have the same hatred that the Jews had; they were less oppressed, and had less to lose under Roman rule. And they were not naturally inclined to fight on the side of the Jews. Even if a leader were to emerge, the Gentiles would not follow a Jew — unless he was the Son of God.

A Jewish rebel, a fellow chandala, but a divine One sent by God — or better, the embodiment of God himself — might be able to win over the allegiance of the unthinking and superstitious Gentile masses. It would be a kind of "charm offensive" against Rome — to steal away their moral authority and place it, ultimately, in the hands of a Jew who would sooth their suffering, and "save" them. "Salvation is of the Jews" (John 4:22), as Nietzsche is fond of reminding us. This sort of stealth insurrection would avoid the kind of direct confrontation that would get the rebels imprisoned or killed, and it would be done in the name of nominally higher values like faith, hope, and love.

Tales of a Jewish messiah come to earth, however, would cause trouble with Paul's fellow Jews. First, the messiah was supposed to save the Jews, not the Gentiles. Second, despite the urgent need, the ancient prophetic signs were not yet in place; any alleged messiah would be false. Furthermore Jesus apparently had a habit of working on the Sabbath, flouting Judaic law. These things were likely the source of Jewish antipathy toward him while he was alive.

The situation demanded a two-pronged strategy. One person — Peter — would work with his fellow Jews to convince them that, yes indeed, this savior would work to the benefit of the Jews; he could be a true "redeemer" after all. The others — Paul, and perhaps Mark, Luke, and others— would undertake to spread the "Good Word" to the non-Jewish masses. How do we know this? Paul tells us himself:

- "Now I am speaking to you Gentiles. Inasmuch as I am an apostle to the Gentiles, I magnify my ministry…" (Rom 11:13);

- "[Jesus was revealed to me] in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles" (Gal 1:16);

- "Let it be known to you that this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (Acts 28:28);

- "[Barnabas and Paul] related what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles" (Acts 15:12).

This conversion of the Gentiles was the core of the overall plan; without them the insurrection would fail: "I want you [Gentiles] to understand this mystery: a hardening has come upon part of Israel until the full number of Gentiles come in, and so all Israel will be saved" (Rom 11:25-26) — saved by the Redeemer from Zion.18 To this end, the doctrine of "original sin" was essential. Every man was condemned from birth, unless he accepted the Jewish savior: "all men, both Jews and Greeks, are under the power of sin" (Rom 3:9); "sin came into the world through one man [Adam] and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned"(Rom 5:12).

Peter's assignment is made clear in Galatians (2:7-8):

I [Paul] had been entrusted with the gospel to the uncircumcised [non-Jews], just as Peter had been entrusted with the gospel to the circumcised [Jews], (for He who worked through Peter for the mission to the circumcised worked through me also for the Gentiles)…

So the plan devised by the ‘Apostle to the Gentiles’ (Paul) and the ‘Apostle to the Jews’ (Peter) was well underway by the mid-50s AD. Nietzsche called it “the most subterranean conspiracy that ever existed” (sec. 62).

As far as we can tell, this small band of Jewish revolutionaries met with marginal success at first. Judging from the near complete lack of written documentation (apart from Paul’s own letters), they had little immediate effect. Once again, the chronology is telling:

Jesus lived for 30-some years; 20 years then passed with no written record at all; and for 20 more years we have only the Pauline epistles. So: 70 years gone by, and the sum total of recorded history for this group of Christian Jews is a handful of letters by their leader, Paul.

And then Paul dies — executed in Rome, so we are told. Coincidentally, it is just at this time (66 AD) that the first Jewish Revolt begins. The battle waxes and wanes for four years, until the Romans prevail in 70, destroying the great Jewish temple at Jerusalem. Suddenly, the game changes. The Jews are annihilated, defeated, and enraged. Their hatred knows no bounds. A burning resentment—ressentiment, according to Nietzsche—gives rise to a maniacal thirst for revenge: "The Romans will pay for this, if it takes a thousand years."

As luck would have it a nascent insurrection was already underway, thanks to Paul and his band of “little ultra-Jews” (sec. 44). Unfortunately, Peter and Mark both died during the Revolt, and with Paul already gone the movement was decapitated. The only survivors were Luke and the chandala apostles Phillip and John.19 Someone then decided to launch a full-court press for Jesus. They decided that the story of his life needed to be written, clearly demonstrating his divine nature. Within a year of the destruction of the Temple, suddenly, miraculously, the Gospel of Mark appears.

As the first detailed account of Jesus, it was crucial that it reach and impress the non-Jewish masses. Hence it was written explicitly for them. Jewish terms and concepts are explained (5:41, 7:1, 13:46, 14:12, 15:42). Jesus employs simple-minded parables (4:10-12, plus many examples throughout). And the book is replete with miracles from the very first page; even the apostles performed them! (6:13). It no doubt had a great effect.20

The Gospel of Mark evidently sufficed, at least for some 10 years. Then, unknown persons for unknown reasons decided to embellish this text, but under different names. Thus came the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. (Again, expert consensus indicates that neither of these were written by their namesakes.) So by the year 90 we have the three "synoptic Gospels" completed, all of which were constructed on a similar plan.

Finally, some time in the final decade of that first century, the Gospel of John appears — again, authorship unknown. It is notably different, both in content and tone, from the other three: no mention of the virgin birth or baptism of Jesus, no "casting out of demons" miracles, clear separation from orthodox Judaism, only rare mention of the suffering and downtrodden peoples, many first-person references by Jesus, and, oddly, Jesus now carries his own cross (previously, Simon). In general, Jesus is portrayed as more thoughtful and philosophical. It seems to have targeted a more upper-class audience, both Jews and non-Jews. Perhaps it was meant as "Christianity for the intellectuals."

By the early 100s, then, everything was in place. All NT books were complete, and they created — literally created — an image of Christ that was compatible with the OT, and, more importantly, suited the larger purpose of winning allegiance from the masses. The Pharisee Jews were not happy, because they understood that this Jesus was a false messiah, but they would come to accept the benefits of a Jewish Christ that could sway the public at large and undermine support for Rome. The plan was brilliant, and by all accounts, it worked. Christianity grew from being persecuted by Rome, to being tolerated under the reign of Constantine (306–337), to being installed as the official state religion by Theodosius in 380 — coincidentally, just 15 years before the disintegration of the Empire.

Of course, it is very difficult to know the extent to which Christianity was a causal factor in the collapse — many other forces were at work, including imperial overstretch, economic inflation, growing attacks by outside powers, barbarization of the Roman military, depopulation from recurrent plagues, environmental degradation, lead poisoning, and corruption within the leadership. Notably, the first modern era account of Rome's collapse — Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1789) — was also the first to cite Christianity and Christian "moral decay" as a leading cause; on this count Nietzsche was not original. Scholars since Gibbon's time generally prefer some combination of the other factors. But the actual cause is not really at issue here. Christianity was certainly very influential during the period of decline, and it undeniably filled the void created when Rome finally collapsed in 476. Even if Christianity was merely the opportunist of the time, Nietzsche's main contention holds.

* * * * *

Whatever the cause or causes, Christianity proved the victor. Unfortunately, says Nietzsche, this victory came at a tremendous cost. The Romans, in fact, had the nobler values. Having absorbed and assimilated the best of classical Greek culture, the Romans of that first century AD were the embodiment of strength, nobility, life-affirmation, and excellence — in short, all that was greatest in humanity.

For the Romans were the strong and noble, and nobody stronger and nobler has yet existed on earth or even been dreamed of: every remnant of them, every inscription, gives delight… (Genealogy, 1.16).

Greeks! Romans! The nobility of instinct, the taste, the methodical research, the genius of organization and administration, the faith in — the will to — man's future, the great Yes to all things, become visible in the imperium Romanum, visible for all the senses, the grand style no longer mere art but become reality, truth, life. (Antichrist, sec. 59)

The Empire could withstand almost anything — "but it was not firm enough against the most corrupt kind of corruption, against the Christians" (sec. 58). They were the revolutionaries and anarchists, pulling on the great pillars of the Empire by draining it of its greatest strength, its system of values:

The Christian and the anarchist: both decadents, both incapable of having any effect other than disintegrating, poisoning, withering, bloodsucking; both the instinct of moral hatred against everything that stands, that stands in greatness, that has duration, that promises life a future. Christianity was the vampire of the imperium Romanum… (ibid.)

The defeat was total. "Which of them has won for the present, Rome or Judea?" Nietzsche answers:

But there can be no doubt: consider to whom one bows down in Rome itself today — and not only in Rome but over almost half the earth, everywhere that man has become tame or desires to become tame: in front of three Jews, as is known, and one Jewess (Jesus of Nazareth, the fisherman Peter, the rug weaver Paul, and the mother of the aforementioned Jesus, named Mary). This is very remarkable: without doubt Rome has been conquered. (Genealogy, 1.16)

When they were defeated, nobility itself was destroyed, and the Jewish chandala morality, the slave morality, arose victorious. For the slaves and Jews this was a happy outcome; for humanity at large it was a catastrophe of the highest magnitude.

How was this attack conducted? First, by countering every aspect of Roman morality and spirituality, and second, by establishing a system favorable to Jewish interests. Against Roman polytheism, the Jews placed monotheism (or "monotono-theism" as Nietzsche would have it). Against a sense of privilege, nobility, and hierarchy, the Jews placed "equality before God", and the notion of "equal rights." Against the ideal of human fulfillment and self-realization here on Earth, salvation now came in the afterlife. Against the gods of nature, who could be cruel and ruthless as well as beneficent, they placed a God of "pure spirit" and love. Against the ideal of bodily strength and vigor, they placed the concept of spiritual health and bodily indifference. Against allegiance to men based upon leadership and the demands of the polity, they placed dependence on the priests. Against truth and reason, they placed lies and faith.

Nietzsche held out particular scorn for the three cardinal virtues of Christianity: faith, hope, and love (Paul, in 1 Cor 13:13). Faith is fundamentally opposed to truth, because one simply "believes" for no rational reason, or worse, in spite of reason; "if faith is quite generally needed above all, then reason, knowledge, and inquiry must be discredited: the way to truth become the forbidden way" (sec. 23). Faith is a "form of sickness, and all straight, honest, scientific paths to knowledge must be rejected by the church as forbidden paths. Even doubt is a sin. … "Faith" means not wanting to know what is true" (sec. 52). It engenders dependency, because one is not allowed to think critically, or for oneself; the believer becomes dependent on the priest, who in turn gains power over the believer. Hence "every kind of faith is itself an expression of self-abnegation, of self-alienation" (sec. 54).

Hope, Nietzsche reminds us, was the one evil that did not escape Pandora"s box. It strikes the modern reader as odd to think of hope as an evil, but in the hands of the Christian it becomes merely "a hope for the beyond" — an unfulfillable (or at least unverifiable) promise of a blessed afterlife. As such, Christian hope is meaningless; worse still, a tool for manipulation, "precisely because of its ability to keep the unfortunate in continual suspense" (sec. 23). To repeatedly promise with no ability to deliver — this is the function of the priest.

Love is the most striking of the three, born as it is, paradoxically, out of Jewish hatred and revenge. Rather than teaching the non-Jews to hate the Romans — for which there was no real basis — Paul and his fellow Jews used "God's love" to seduce the masses. This necessitated, first of all, a certain conception of God: "To make love possible, God must be a person," not merely some abstract metaphysical entity. To truly personalize God, he must come to Earth in human form — hence Jesus. "Jesus" (of the Pauline persuasion) now serves a specific purpose: to allow us to "love God" more easily. Once we are in love, we both tolerate more, and are ripe for manipulation. "Love is the state in which man sees things most decidedly as they are not. … In love man endures more, man bears everything" (ibid). So once the masses are drawn to the Jewish Messiah by love, they accept what he says unquestioningly, and are willing to submit to trials and hardship — a perfect combination for the Jewish priest. Accept the Jews, those chosen people of God; don't resist the Jews; love thy neighbor, the Jew (Rom 13:9) — this is the message:

The Christian…is distinguished by acting differently: by not resisting, either in words or in his heart, those who treat him ill; by making no distinction between foreigner and native, between Jew and non-Jew ("the neighbor" — really the coreligionist, the Jew); by not growing angry with anybody, by not despising anybody… (sec. 33)

Because the goal was to convert and mobilize every available person, Jesus (God) must love all people equally. Paul thereby negated one of the most ancient realities of human society — the hierarchy of rank among individuals — with his doctrine of a God that gives his blessing to all. He also negated the existence and importance of ethnic and national differences and conflicts among different ethnic and national interests:

All people are essentially the same in the eyes of God. All men have an immortal soul that can be saved, and thus are inherently equal: "For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body — Jews or Greeks [i.e. non-Jews], slaves or free — and all made to drink of one Spirit" (1 Cor 12:13); "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Gal 3:28). In Nietzsche's paraphrase, "Everyone is the child of God…and as a child of God everyone is equal to everyone."

There could scarcely be a more pernicious lie than this, he argues. If no one is worse than anyone else, then no one is better — no one can get better. This is counter to the whole thrust of life and evolution, which is toward the greater, the higher, the more refined, the nobler. But it is as necessary as it is destructive, if the masses are to be mobilized. Thus emerged the slave morality of the Christians, out of the hatred and revenge of the Jews. And it was all based upon lies: the lie of equality, the lie of the miracle, the lie of the resurrection, the lie of God, the lie of Christian love. It is so profoundly opposed to nature and the natural order of the world that it creates a deep sickness within humanity. This "world of pure fiction" and its "hatred of the natural…of reality!" actually has an interest in creating a sickness that only it can assuage:

Christianity needs sickness just as Greek culture needs a superabundance of health — to make sick is the true, secret purpose of the whole system of redemptive procedures constructed by the church. (sec. 51)

Christianity also stands opposed to every spirit that has turned out well; it can use only sick reason as Christian reason, it sides with everything idiotic, it utters a curse against the spirit, against the superbia of the healthy spirit…Sickness is of the essence of Christianity. (sec. 52)

The sickly, the weak, the enfeebled, the ignorant, the repugnant — we know these are the essence of a Jewish-contrived Christianity because…Paul tells us:

God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are… (1 Cor 1:27-28).

"This was the formula," says Nietzsche; under this sign, "decadence triumphed" (sec. 51). This, in a single passage, contains the essence of Christian depravity and decay.

Decadence is only a means for the type of man who demands power in Judaism and Christianity, the priestly type: this type of man has a life interest in making mankind sick, and in so twisting the concepts of good and evil, true and false, as to imperil life and slander the world. (sec. 24)

In Christianity all of Judaism, a several-century-old Jewish preparatory training and technique of the most serious kind, attains its ultimate mastery as the art of lying in a holy manner. The Christian, the ultima ratio of the lie, is the Jew once more — even three times a Jew. (sec. 44)

Nietzsche closes Antichrist with guns ablaze:

Paul, the chandala hatred against Rome, against "the world," become flesh, become genius, the Jew, the eternal Wandering Jew par excellence. What he guessed was how one could use the little sectarian Christian movement apart from Judaism to kindle a "world fire"; how with the symbol of "God on the cross" one could unite all who lay at the bottom, all who were secretly rebellious, the whole inheritance of anarchistic agitation in the Empire, into a tremendous power. "Salvation is of the Jews."Christianity as a formula with which to outbid the subterranean cults of all kinds…and to unite them: in this lies the genius of Paul. His instinct was so sure in this that he took the ideas with which these chandala religions fascinated, and, with ruthless violence, he put them into the mouth of the "Savior" whom he had invented… This was his moment at Damascus: he comprehended that he needed the belief in immortality to deprive "the world" of value, that the concept of "hell" would become master even over Rome — that with the "beyond" one kills life. (sec. 58)

The whole labor of the ancient world in vain…the whole meaning of the ancient world in vain! Wherefore Greeks? Wherefore Romans? All the presuppositions for a scholarly culture, all scientific methods, were already there… Everything essential had been found, so the work could be begun… All in vain! Overnight, nothing but a memory! … [R]uined by cunning, stealthy, invisible, anemic vampires. Not vanquished — merely drained. Hidden vengefulness, petty envy become master. Everything miserable that suffers from itself, that is afflicted with bad feelings, that whole ghetto-world of the soul on top, all at once. (sec. 59)

Parasitism as the only practice of the church; with its ideal of anemia, of "holiness", draining all blood, all love, all hope for life; the beyond as the will to negate every reality; the cross as the mark of recognition for the most subterranean conspiracy that ever existed — against health, beauty, whatever has turned out well, courage, spirit, graciousness of the soul, against life itself. … I call Christianity the one great curse, the one great innermost corruption, the one great instinct of revenge, for which no means is too poisonous, too stealthy, too subterranean, too petty — I call it the one immortal blot on mankind. (sec. 62)

What an incredible feat: to turn Europeans away from their own western heritage — a noble, life-affirming Greco-Roman culture — and toward a foreign, alien, decadent, Oriental worldview. And it was done as revenge, out of hatred, and built upon lies. An ancient religion — Judaism — born of falsehood and lies, creates another born of falsehood and lies. It is done for reasons of power, control, wealth, and survival. And the lie prevails.

Judaism never did fully accept Christian morality or the notion of a Christian Messiah — even if he were a Jew. Though there was considerable overlap in the two religions — both are variations on the slave morality — Judaism retained its insularity, suspicion of Gentiles, need for control, exploitation, and power, and inclination for revenge. As Christianity took flight it became, of course, a non-Jewish religion. Christian morals thus emphasized compassion, love, "resist not evil", "turn the other cheek", "blessed are the meek." There could obviously be no suspicion of non-Jews within Christianity, but this was replaced by a suspicion of all that was great, strong, and noble — the exemplar, the outstanding individual who put the lie to the notion of universal equality.

Implications for the Contemporary Scene

So what are the consequences of all this for today? There are many, of course. If indeed the essence of Pauline Christianity is sickness, and if it indeed is anti-natural and neglects all that is healthy and strong, then we should see some tangible evidence of this. For example, given that ultimate value lies in spiritual salvation, we might expect that the more pious, church-going nations would have less concern about bodily health. And in fact there seems to be a correlation between the two. Using obesity rates as a rough measure of physical health, an analysis of public survey data shows that the most religious Christian nations are also the most obese. Specifically, about 60 percent of the people in the U.S. and Mexico consider Christianity "very important," and these same two nations have the highest obesity rates — 30 and 25 percent, respectively. Conversely, France, Germany, and the Czech Republic are less than 20 percent religious, and are also less than 15 percent obese.21 Of course, correlation is not causation, and we cannot say that Christian beliefs cause or promote ill health. But even if the converse is true — if the sick, the ill, the obese are drawn to Christianity — this does not speak well for the religion. Either way Nietzsche's point appears confirmed: Physical health is not a big deal; God loves us no matter what.

But on more philosophical points, four items in particular stand out as clear implications. First, a heavy emphasis on freedom. The Judeo-Christian slave morality arises from an extreme lack of personal and social freedom, and thus it should exhibit a clear preoccupation, or even obsession, with freedom. This seems transparently clear in the U.S., at least, where "liberty" is a core value, along with "life" and "happiness." One recalls President Bush (Jr.)'s 2002 State of the Union speech, peppered with some two dozen references to it. We could point to our "war on terror," of which a prime objective is to "bring freedom" to the oppressed. We could cite our military adventurism in the Middle East, with its "Operation Iraqi Freedom" and "Operation Enduring Freedom" (Afghanistan). Our leading enemies in the world today are those who "hate our freedoms."

The current, popular, governmental form of freedom is a debased concept. It is a freedom of capitalism, a freedom of exploitation, and a decadent, soft, amoral form of personal freedom; "liberalism," as Nietzsche would have it. Liberal institutions

undermine the will to power, they set to work leveling mountains and valleys and call this morality, they make things small, cowardly, and enjoyable — they represent the continual triumph of herd animals. Liberalism: herd animalization, in other words… (Twilight of the Idols, sec. 38).

True freedom, in Nietzsche's view, is something different. It is the Greco-Roman conception of the idea — something felt, something lived. The Greeks and Romans did not speak of freedom or rights at all. They were free, they lived as free men, and thus did not obsess about it. And this is precisely the point: A truly free people does not obsess about freedom, or about rights. Only those enslaved, or those laboring under a slave morality, continue to do so. True freedom, Nietzsche says, is the struggle to maintain one's personal independence and integrity in the face of countervailing forces. "What is freedom? Having the will to be responsible for yourself. Maintaining the distance that divides us. Becoming indifferent to hardship, cruelty, deprivation, even to life. … A free man is a warrior" (ibid).

Second, the natural extension of "equal before God" is "equal before the law". This implies a natural affinity to both democracy and equality of rights. Democracy is contemptuous precisely because it is the politics of the herd; it finds sustenance in the Judeo-Christian herd morality: "the democratic movement is the heir of the Christian movement" (Beyond Good and Evil, sec. 202). For Nietzsche, "the democratic movement is not only a form of decay of political organization but a form of the decay, namely the diminution, of man, making him mediocre and lowering his value" (ibid: 203). The Roman Empire flourished because it was anti-democratic.

On the general critique of democracy, Plato was in full agreement. For him (as for Aristotle), democracy was rule by the uneducated masses, and hence the lowest common denominator. Consequently it was nearly the worst form of government — surpassed only by tyranny.22 The pre-Christian world knew that brute democracy was something to be avoided.

Of course, the mere adoption of a Christian morality did not ensure democracy — as demonstrated by the Byzantine Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, and the many Renaissance dynasties of Europe. Nor is it the only path to modern democracy — witness the Hindu democratic system in India. But for Europe at least, large-scale industrial democracy was the "heir" to Christianity, and it took several centuries to become manifest. It represents only the latest stage in the decline of western man.

The other implication of spiritual equality is that of equal rights. "The poison of the doctrine of "equal rights for all" — it was Christianity that spread it most fundamentally" (sec. 43). It was a kind of gross flattery to tell even the lowest of the low — the chandalas, the masses — that they were equal to the highest, and deserved equal standing; this "miserable flattery of personal vanity" was a key element in the success of Christianity. It created the herd, and the herd would be led by their divine Shepherd. But this is not reality. In the real world there is order of rank, of lesser and greater individuals. Rights based on meaningless equality are themselves meaningless. Men are by nature unequal, and thus the only possible rights are those appropriate for each station — in other words, of unequal rights: "The inequality of rights is the first condition for the existence of any rights at all" (sec. 57). Rights are something one holds against another; when all have them, none have them.

Convinced of his equality and his rights, the chandala is willing to fight for them. Here the Christian rebel takes to work, inciting the masses against those stronger and nobler who would deny their equality — yet another justification for Nietzsche's contempt:

Whom do I hate most among the rabble of today? The socialist rabble, the chandala apostles, who undermine the instinct, the pleasure, the worker's sense of satisfaction with his small existence — who make him envious, who teach him revenge. The source of wrong is never unequal rights but the claim of "equal" rights. … The anarchist and the Christian have the same origin. (ibid)

The passions of the common man are inflamed, envy is fostered, and the result is discontent. Once the hierarchy of the strong (e.g. the imperium Romanum) is undermined, then the herd becomes the dominant force. It is thereby easily manipulated by the priestly shepherds.

Thirdly, under the dictate of equality of all men, and the moral prescription to love thy neighbor, one is compelled to accept some form of multiculturalism, and even cultural relativism. All of humanity is part of the great Christian herd, at least potentially so. Those not explicitly Christian are converts-in-waiting. God does not discriminate amongst souls, nor should we. All are welcome to our flock; the bigger the herd, the better.

Finally, the primary goal of the whole scheme: benefit to the Jews and the Jewish state. In this sense we have, on the whole, and in spite of periodic pogroms throughout the centuries, a tremendous success story for the Jewish people. It cannot be anti-Semitic to point this out. In fact it is to their credit that such a small and beleaguered people could achieve such influence in an uncertain and dangerous world.

Especially in recent times, Jews have profited immensely from public sympathy — a sympathy frequently rooted in Christian theology. With Christianity, "we are among Jews": Christ, the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, "salvation is of the Jews" — even God is a Jew:

When the presupposition of ascending life, when everything strong, brave, masterful, and proud is eliminated from the conception of God; when he degenerates step by step into a mere symbol, a staff for the weary, a sheet-anchor for the drowning; when he becomes a god of the poor, the sinners, and the sick par excellence…just what does such a transformation signify? To be sure, the "kingdom of God" has thus been enlarged. Formerly he had only his people, his "chosen" people. Then he, like his people, became a wanderer and went into foreign lands…until "the great numbers" and half the earth were on his side. Nevertheless, the god of "the great numbers," the democrat among the gods, did not become a proud pagan: he remained a Jew, he remained a god of nooks, the god of all the dark corners and places, of all the unhealthy quarters the world over! (sec. 17)

Hence: to love Christ and to love God is to love God's chosen, the Jews — an ideal situation, if you're Jewish. How much the easier to exploit the sympathies of the masses; to curry favor and gain support; to manipulate and mislead. And as before, survey data show that the more Christian the nation, the greater its sympathy to Israel and Jews generally.23

As a practical consequence, Americans in particular seem satisfied to allow Jewish-Americans an unprecedented and hugely disproportionate role in their nation — in other words, to be their shepherds. Though less than 2 percent of the population, American Jews are extremely influential in the cultural and economic life of the nation.24 Likewise in the political sphere, where the Israel Lobby — led by AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) and the CoP (Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations) — wields immense power.25 The end result is that, through a hammer-grip on the American superpower, Jewish and Israeli interests are able to influence events throughout the world. As former Malaysian president Mahathir Mohamad said, "Today Jews rule the world by proxy. They get others to fight and die for them." Indeed — the sheep must occasionally be led to slaughter.

And yet…the system is not perfect. There is, as we know, a lingering anti-Semitism within Christianity. Some are angry that "the Jews killed Christ." Many dislike their dominance and corruption of American society. Others are dismayed at the criminal actions of Israel in the occupied territories. They are upset by the virtual apartheid that exists there today, the anti-Arab discrimination, and the driving out of Christians from the holy land. People are unhappy with Jewish manipulation of media and entertainment, with the billions of dollars in annual foreign aid to Israel, with the costly wars in the Middle East that serve primarily to protect Israel — and yet they cannot bring themselves to openly oppose the Jews. Such internal conflict is easily manifest in various forms of anti-Semitism.

I wonder if many Christians don't somehow know, deep inside, that their very faith is based on Jewish lies and resentment. I wonder if they know they have been duped. There are also, perhaps, subconscious worries that, just maybe, other popular legends might also be fanciful exaggerations built on hatred and lies.26 When governmental and institutional leaders have proven themselves corrupt and unreliable, and occasionally outright liars, then one does not know whom to trust.

Even if Nietzsche was right — if Christianity was in fact "the most subterranean conspiracy that ever existed" — it still cannot go unexposed forever. People seem to be more willing than ever to challenge age-old (and not-so-old) religious myths. Perhaps the accumulated sense of manipulation, illness, and moral decadence will cause people to break out of their stupor, ask tough questions, and demand real answers. If so, then Dr. Nietzsche will have earned his keep.

Dr. Thomas Dalton is the author of Debating the Holocaust (2009).

Notes to Part 11] Hinduism is number three, with about 900 million adherents, although those professing atheism or holding other explicit non-religious views are greater in number, now about 1.1 billion.

2] For a detailed study of Nietzsche’s complex views on Jews and Judaism — see my article, “Nietzsche on the Jews.”

3] Most of the following quotations are from Antichrist, and this book is the source where I have indicated only section numbers. Quotations from other books will be explicitly cited.

4] According to legend, Abraham had two sons: Isaac, who gave rise to the Jewish lineage, and Ishmael, the father of the Arabs.

5] Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

6] The following quotes are from his article “Deconstructing the walls of Jericho”, Ha’aretz Magazine, October 29, 1999.

7] “Most historians today agree that, at best, the stay in Egypt and the exodus events occurred among a few families, and that their private story was expanded and ‘nationalized’ to fit the needs of theological ideology.” There is one later Egyptian documentation of such an event, by the high priest Manetho from the third century bc, which comes to a similar conclusion. As recounted by Lindemann, “the Jews had been driven out of Egypt because they, a band of destitute and undesirable immigrants who had intermarried with the slave population, were afflicted with various contagious diseases.” The Jews were thus expelled “for reasons of public hygiene.” In sum, “the account in Exodus was an absurd falsification of actual events, an attempt to cover up the embarrassing and ignoble origin of the Jews.” (Esau’s Tears, 1997: 28).

8] A History of the Jewish People (Harvard University Press; 1976), pp. 254-255.

9] Future emperor Titus led the Roman attack. His victory was commemorated with the construction of the Arch of Titus, a striking monument that stands today aside the Colosseum.

10] With the notable exception of Paul — details to follow.

11] The sole exception is an incident recorded in Luke (2:41-51), in which a 12-year-old Jesus escapes from parental oversight and is later found in the company of some spiritual teachers. Certainly nothing miraculous about that.

12] As we recall: John, Matthew, Peter (aka Simon, aka Cephas), Andrew, James the Greater, James the lesser, Phillip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Jude (aka Thaddeus), Simon, and Judas.

13] This fact should be widely known by now, but it’s not. Even a quick glance at an encyclopedia confirms it: “Today, many scholars doubt that any of the writers of the Gospels knew Jesus during his lifetime. They also doubt that we know the actual names of the writers.” (World Book Encyclopedia, 2003, ‘Jesus Christ’)

14] See Philippians 3:5, and Acts 23:6 or 26:5.

15] Seven of these 13 are considered to be genuinely authored by Paul; the other six are disputed.

16] In another biblical oddity, one would expect details of his death to be recorded in Acts, which is otherwise so detailed about Paul’s life. This is especially true given that this book dates to the years 80-100, well after his alleged execution. But it stops just short of describing his death.

Notes to Part 2

17] Notably, "Barnabas." See Acts 14 and 15.

18] The passage in Romans continues: "The Deliverer [Redeemer] will come from Zion," referring to the OT prophecy that "deliverance for Israel would come out of Zion" (Ps 14:7). See also Isaiah 59:20.

19] Thomas is alleged to have lived a couple more years, until 72. And several of the other apostles have unknown deaths, and thus may have been alive somewhere.

20] Lindemann (Esau's Tears, 1997: 31) describes it this way: "Both Paul and the writers of the Gospels radically redefined the traditional Jewish notion of messiah, from [an ordinary man] to that of a supernatural figure much resembling the dying and reviving salvation gods that were common to many pagan mystery cults of the day. There were certainly many overlaps between those cults and early Christianity."

21] Obesity data from "Religious attitudes are reported in the Pew Global Attitudes Project," 19 December 2002. Data from nine nations shows a strong linear correlation (R2 value = 0.58). Interestingly, the correlation between obesity and religiosity seems not to be found in Islam; Turkey, for example, is very religious (65% consider it "very important"), but has only a 12% obesity rate.

22] For Plato's critique see Republic, Book 8. In his view aristocracy was the ideal form, followed by timocracy and oligarchy; democracy and tyranny were the worst. Aristotle saw democracy as a degenerate form of "rule by the masses"; see Politics, Book 3. This may strike some as odd, given ancient Greece's reputation for having invented democracy, and thriving because of it. And relative to barbarism or anarchy, it was superior. But it works best as participatory democracy, in a very small state. Large, modern nation-states, of the kind Nietzsche considered, brought out the worst aspects of democracy.

23] As the most religious nation (59% "very important"), the U.S. is also most sympathetic: 48 percent of the population sympathizes more with Israel in the conflict in Palestine (Pew Research survey, 19 July 2006), a figure that rises to 57 percent among Christian Zionists. Conversely, the European countries are both less religious and less sympathetic to Israel (which run 38 percent in France, 37 percent in Germany, 24 percent in the UK, 9 percent in Spain).

24] According to Vanity Fair (October 2007), they make up more than half of the "100 most powerful people" in the world. Of the top 400 richest individuals in the U.S., at least 149 (37%) are Jewish (top 400 reported in Forbes, 30 September 2009; Jewish count by Jacob Berman, (www.blogs.jta.org) [5 October 2009]). Fully half of the top 50 political pundits are Jewish (top 50 list from Atlantic, September 2009; Jewish count by Steve Sailer [www.isteve.blogspot.com). In media and entertainment the dominance is almost total. Jewish executives lead all five of the top U.S. media conglomerates — Time-Warner (Jeff Bewkes, Edgar Bronfman), Disney (Robert Iger), News Corp (Rupert Murdoch, Peter Chernin), Viacom (Sumner Redstone, Leslie Moonves, Philippe Dauman), NBC-Universal (Jeff Zucker). All are Jewish except possibly Murdoch. Six of the top seven American newspapers have Jewish management. Virtually every major Hollywood studio exec is Jewish — see "How Jewish is Hollywood?", Los Angeles Times, 19 December 2008.

25] In the political sphere, Jewish-Americans comprise 7 percent of the House and 15 percent of the Senate. Even more impressively, some 80 to 90 percent of both chambers reflexively support Jewish interests. The reason: pro-Jewish individuals and lobbies supply half or more of political campaign contributions — for both major parties; see "Candidly speaking: Obama, Netanyahu and American Jews" Jerusalem Post (11 May 2009). The lobby AIPAC is among the top two or three most powerful in Washington, and they have absolute dominance in U.S. foreign policy. All major presidential candidates bend over backward to placate Jewish interests. For details on the American political scene, see Mearsheimer and Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy (2007).

26] The Holocaust and the 9/11 attacks being the prime examples. For the Holocaust, see my book Debating the Holocaust: A New Look at Both Sides (www.debatingtheholocaust.com) or G. Rudolf, Lectures on the Holocaust. On the 9/11 controversy, see D. Griffin, Debunking 9/11.

http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/authors/Dalton-Nietzsche2.html