The Christian Reinterpretation of Beowulf

Revilo Oliver

IN ONE OF THESE "Postscripts," published in May 1986 (**), I described briefly one ominous symptom of the growing epidemic of unreason among scholars, an attempt to Christianize the oldest monument of English literature by atrocious mutilation and interpolation of the Anglo-Saxon text.

Now I learn from a review in Speculum, LXI (1986), pp.668-670, that another attempt to distort for Jesus the fundamentally pagan epic was made by Professor Bernard F. Huppe of the State University in Binghamton, New York, in The Hero in the Earthly City, a Reading of Beowulf, published by that university in 1984.

I have not looked at the book. As it is, to report incidents that seem to me noteworthy to the readers of Liberty Bell, I afflict myself by reading so much tripe that I am beginning to wonder whether I should be so supercilious when I refer to the Christian dolts who used to wear horsehair shirts to make themselves suffer.

I rely entirely on the review by Professor Edward B. Irving, Jr., who notes various errors of fact in the book and also remarks on the absurdity of an "Augustinian" interpretation of the poem. Huppe seems not to have tampered overmuch with the Anglo-Saxon text, but, as the reviewer remarks, he "smuggles in the Christian concept of grace" by simply giving to the Anglo-Saxon words meanings they could not possibly have had. "A tidy Christian poem is reconstructed from the ruins of its proper original contexts, … and the pressure to distort is constant." Having thus Christianized the poem, Huppe then denounces its failure to adhere to his favorite theology: Beowulf ought to have remembered that Jesus said revenge was sinful, and he sins terribly by fighting the dragon without getting Yahweh's permission.

The details of the travesty do not matter. As I said in my "Postscript," the Anglo-Saxon epic is fundamentally and unmistakably a pagan composition, and the only question is who introduced the bits of Christian or ambiguous phraseology that are found here and there in our only extant text and are as conspicuous and incongruous as patches of red calico on a dinner jacket. Everyone knew that in 1920, when what is still the best edition of the text and commentary was published, and it is only sheer perversity to pretend otherwise today and use the methods of scholarship to defeat the very purpose of scholarship.

The pernicious factor in such misbegotten studies is their effect, not on scholars who have read and understood the poem, but on students in cognate fields, who may have to rely on the reports of "specialists" in Anglo-Saxon. A multiplication of books that distort the epic is apt to create an impression that "modern scholarship" has discovered that it sprang from a Christian society. And that application of the "democratic" principle of ascertaining truth by counting noses will deceive many earnest students and may confuse or even vitiate some of their work in their own fields of research.

Academicians want to be fashionable, and it is likely the next few years will bring us more "studies" that affirm the factitious Christianization of our earliest extant monument of English literature, but that, of course, will prove nothing. It will be as meaningless as the Jews' current efforts to shore up their crumbling Holohoax by producing more and more Yids, who pop out of the bushes and suddenly remember that they watched the wicked Germans cram millions of God's Darlings into gas chambers or ovens, it being assumed that the notoriously methodical Germans inexplicably and unforgivably forgot to include the watchers with their fellow tribesmen. Lies do not become truth by multiplication. 50,000 x 0 = 0.

The continuing flurry of "critical reinterpretations" of Beowulf is symptomatic and highly signficant because it is, in a way, so comparatively trivial. The number of persons who read Anglo-Saxon is very small, and I cannot believe that multitudes are reading one or another of the translations into modern English. And does it really matter whether or not the poem is basically "pagan"? Is not that just a bit of antiquarian lore, comparable, for example, to identification of the corpse in the famous ship-burial at Sutton Hoo, interesting, no doubt, to some people, but of no relevance to the present?

That is precisely my point. If these were efforts to deceive Americans about something that will affect their thinking (such as it is) about their present plight, the explanation would be obvious. Manufacture of "evidence" to support the Jews' great swindle, or production of a revelation that Karl Marx was, like Jesus, an avatar of old Yahweh, or even endorsement of the prevalent hokum about what is mendaciously called our Civil War, would have an obvious purpose.

If a man labors long to devise and perfect an elaborate swindle that will net him a billion of the ersatz-dollars now in use, we understand and have no more doubts about his rationality than about his morality. But if he makes the same prolonged and arduous effort to filch a dime, he is a problem in psychonosology. The contagion of unreason among scholars is so ominous and frightening precisely because it is so gratuitous.

This article originally appeared in Liberty Bell magazine, published monthly by George P. Dietz from September 1973 to February 1999.

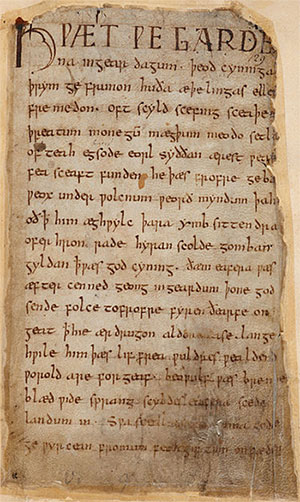

* see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nowell_Codex#/media/File:BLBeowulf.jpg** Liberty Bell, POSTSCRIPTS May 1986

THE FLIGHT FROM REASON

by Revilo P. Oliver

I have had to comment from time to time on the "creation scientists," who are one of the most ominous phenomena of our darkling age. They are alarming because they are not professional theologians, marketing their "transcendental" wares, nor yet ignorant crackpots, like the inspired tailor, Lodowicke Mugleton, or the recalcitrant housewife, "Mother Ann" Lee. They are men who have been trained in the techniques and, one would suppose, the principles of scientific research, but perversely use their academic credentials to promote unmistakable hoaxes, such as the "Holy Shroud," or to concoct pseudo-scientific verbiage in support of the Jews' rifacimento of the Babylonian creation-myth.

They are not an isolated phenomenon. The same strange lust for sciolistic mystery-mongering to promote old Yahweh appears, I am sure, in every domain of learning. I could cite scores of examples in widely varying fields of scholarship. Most recently, I was close to incredulity when I read the review in Speculum, LX (1985), pp. 755f., of a recent book by Professor Raymond Plummer Tripp, Jr., which bears the cute title, More About the Fight with the Dragon, Beowulf 2208b-3182: Commentary, Edition, and Translation (Lenham, Maryland, University Press, 1983). I borrowed a copy of the book. It amazed me.

The Anglo-Saxon epic, Beowulf, is commonly described as our "most precious relic of early Germanic literature." It presents a multiplicity of problems that have exercised scholars since it was first published under the title (in Latin, in conformity with scholarly practice at that time), De Danorum Rebus Gestis Secul. III & IV. ; Poëma Danicum Dialecto Anglosaxonica. Copenhagen: Th. E. Rangel, 1815. First Edition. 1st edition (in both Old English and Latin) of the Anglo–Saxon epic.

That title advertises the first problem. It is a poem written in England about the deeds of heroes who lived in Denmark and the southern district of Sweden known as Gotland, It is an English poem that has nothing to do with England, which is not even mentioned. Was it originally written in Denmark or Sweden, so that our text is an Anglo-Saxon translation or adaptation of a Norse epic now lost?

Most scholars are certain that Beowulf was composed in Anglo-Saxon in the seventh or eighth century, one or two centuries after the events narrated ia it were supposed to have taken place. Presumably the poet composed his verse for the satisfaction of English noblemen who were interested in the exploits of their racial kinsmen across the German Ocean (now called the North Sea).

The text s preserved in only one manuscript, copied around the year 1000, by two scribes, neither of whom was competent in the Anglo-Saxon of the poem, which had become archaic by their time, and which they copied as prose; they were further distracted by tlieir effort to write a clear, regular hand and produce neat, even elegant, pages. The manuscript was damaged by fire in 1731, before anyone had made a study of the text or even copied it, and after that the scorched or charred margins of many pages broke off and were lost in handling.

The Wyatt-Chambers edition of the text (Cambridge University Press, 1920) includes photographs of pages that illustrate the markedly different hands of the two scribes and also will show you how the pages were damaged in a fire that almost deprived us of the oldest monument of English literature. (This edition, with the companion volume, R.W. Chamber's Introduction, is, I believe, the most useful edition of the Anglo-Saxon and I recommend it in preference to the later editions, which were made to present debatable emendations or to accompany English translations.)

Generations of scholars have labored to purge the text of scribal errors, restore the words that were lost when the margins were destroyed, and fix the meaning of a few words that are rare or even hapax legomena, probably because Beowulf is the only poem of its kind that has survived to our time. There will always be some points at which scholars will debate the correct reading of a word or inflection, but these are minor or even minute details that are of virtually no importance when one considers the poem as a whole.

It is absolutely certain that the poem is essentially a pagan work. It narrates the exploits of a Norse hero and his associates in a world unperturbed by Christianity, although someone—whether the author or a subsequent copyist is much disputed—made a few interpolations here and there to add an explicit but incongruous Christian coloring and quite probably altered a few words that had a specifically pagan rehgious connotation, e.g., replacing "wyrd" (fate) with "god", a word which need mean only a god (unidentified), but which was cleverly used by Christians as a specific reference to their own compound deity.

On the basically pagan nature of the poem, all scholars have been in complete agreement. The debate has been over the question whether it is more probable that the author was (1) a pagan with whose work a Christian scribe or editor tampered here and there ad maiorem Dei gloriam, or (2) a man who, like the famous Snorri Sturluson, was at least publicly a Christian, but felt the profound attraction of his native religion and mythology and tried to preserve it, and so composed in Anglo-Saxon a long poem about the exploits of pagan heroes, inserting here and there some Christian coloring, perhaps as a prudent precaution against the Christian lust to persecute.

Now comes Professor Tripp modestly to assure us that all scholars of Anglo-Saxon have thus far been groping blindly in the darkness of a polar winter—a darkness that has at last been dispelled, now that the sun of his intellect has risen above the horizon. Claiming that our text is fantastically corrupt, he has "rectified" it by rewriting the last thkd of the poem. You won't recognize it as coming from any poem you ever read.

Most of what you remember from that part of Beowulf is gone. Professor Tripp has expunged the dragon, the fugitive slave, Wiglaf (Beowulf's faithful man-at-arms, who adds such pathos to the end of the story), and many minor characters and incidents. There is still someone named Beowulf, but he has been transformed into an entirely different man. The fiery dragon has been replaced by an evil king, a pagan who, by Satanic arts, has returned to life after death to harass good Christians. There is no dragon's horde and no fugitive slave who steals a jeweled goblet. It is the reanimated but unregenerate pagan himself who steals a sacred goblet from Beowulf!

And Beowulf is a Christian hero who combats the vile heathen's diabolically reanimated body on behalf of good old Jesus and the True Faith. Hallelujah and pass the holy water!

Make no mistake: this big book is a work of great learning. There can be but few scholars whose knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon language excels Tripp's. He explains each of his innumerable and drastic alterations of the text as an emendation, for which he gives a plausible explanation by the rules of palaeography, involving one or another of the many elaborately classified causes of scribal errors in copying.

On strictly palaeographic grounds, i.e., without regard to the resulting meaning in its relation to the rest of the poem, each single "emendation" is possible in itself; it is in the aggregate that they become so preposterous that it is hard to speak of them without ridicule. One is tempted to say that if the text has been so corrupted as to require all of his drastic "rectifications,"we have no means of knowing what the poem was about—perhaps the subject was Mary's little lamb or the hunting of the snark. A man with Tripp's knowledge of Anglo-Saxon and palaeography could, with only a little more effort, "rectify" the text to introduce those subjects, and his text would be as linguistically and palaeographically substantiated as Tripp's new Beowulf—and only a little more remarkable as a perverse use of great erudition to violate common sense.

Years ago, a beamish adolescent, subsidized by a wealthy man in California, boasted in print that he was "hooked on Jesus." Capricious or derelict youngsters are commonplace these days, but when philologists become hooked on the same drug, it is time to become more alarmed than ever for the future of civilization.

_____LIBERTY BELL The magazine for Thinking Americans, is published monthly by Liberty Bell Publications.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH-FREEDOM OF THOUGHT FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

The editor-publisher of Liberty Bell does not necessarily agree with each and every article in this magazine, nor does he subscribe to all conclusions arrived at by various writers; however, he does endeavor to permit the exposure of ideas suppressed by the controlled news media of this country. It is, therefore, in the best tradition of America and of free men everywhere that Liberty Bell strives to give free reign to ideas, for ultimately it is ideas which rule the world and determine both the content and structure of culture. We believe that we can and will change our society for the better.

We declare our long-held view .that no institution or government created by men, for men, is inviolable, incorruptible, and not subject to evolution, change or replacement by the will of the people. To this we dedicate our lives and our work. No effort will be spared. and no idea will be allowed to go unexpressed if we think it will benefit the Thinking People, not only of America, but tlie entire world.

George P. Dietz, Editor & Publisher